If there’s one main idea driving excitement in the “creator economy,” it’s this: Creators with large audiences on platforms like Instagram, TikTok, Twitter, and YouTube could generate orders of magnitude increases in revenue if they had better ways to charge fans for content directly, rather than relying on ads or merch sales.

A wave of startups has emerged to build this dream, helping creators sell all formats and genres of content. In some cases, this playbook works fantastically well: OnlyFans, Patreon, Substack, Teachable, Twitch, and many more are helping hundreds of thousands of creators earn a living. And thanks to that success, incumbent networks like Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube have responded with user-pay features of their own.

But there’s one critical step I see missing over and over again, from tiny startups to the world’s biggest incumbents: forgetting to sell. In the scramble to build frictionless payment mechanisms, the actual pitch — the “here’s why you should subscribe/pay/join, and here’s what you’re paying for” — is an afterthought, and the responsibility is often relegated to the creator.

There’s a common misconception among creators and creator platforms that getting a fan to pay for content is basically just a stronger version of hitting the “follow” button. But following a person on Twitter or YouTube and paying for the privilege are two very different things that require very different marketing and acquisition mechanisms. More attention must be paid to the sales funnel — and platforms need to build out the features for creators to effectively make the sell.

A pattern of under-selling

In the past, “paid content” business models were largely tested by startups that lacked a pre-existing network of engaged users. Back then, it was easy to blame gloomy conversion rates on the cognitive friction required to drive fans to a new and unfamiliar platform.

But successful platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube don’t have a problem with engagement. I suspect the real issue, in these cases, is the basic blocking and tackling involved in good marketing. It’s easy to forget, but even the most popular creators need to sell in order to get fans to buy.

It’s often said that creators today need to be CEOs — the chief executives of their own enterprises — even if they draw on outside resources or tools for help. Understanding one’s business and directing that strategy shouldn’t mean creators have to do all the business development themselves, however. In the same way that technical startup CEOs will always have to sell, so do creators. And platforms need to help them.

It’s one thing to create engaging free content, but it’s a totally different thing to conceptualize a value proposition, create effective marketing messages that communicate that value proposition, and get those messages in front of fans at the right time, repeatedly. This, in my experience, is the main thing creator platforms are most likely to get wrong. In my time building products for Gimlet, Substack, and Every — analyzing creator tools and subscriber flow — I’ve catalogued common missteps, as well as overlooked sales strategies. Below, I share some case studies of what I call the under-sell, as well as observations on how platforms can better support creators.

Sales funnel case study: Twitter Super Follows

Twitter is one of the most dominant free networks, but it has only recently begun to offer payment capability. This provides one salient example of a creator platform that undersells the pitch. The company recently introduced the “Super Follows” feature, in which users can pay to receive bonus content from accounts they love. The service launched in early September, starting with dozens of creators who have millions of combined followers. But in its first two weeks, those creators only generated $6,000 in combined revenue, according to SensorTower.

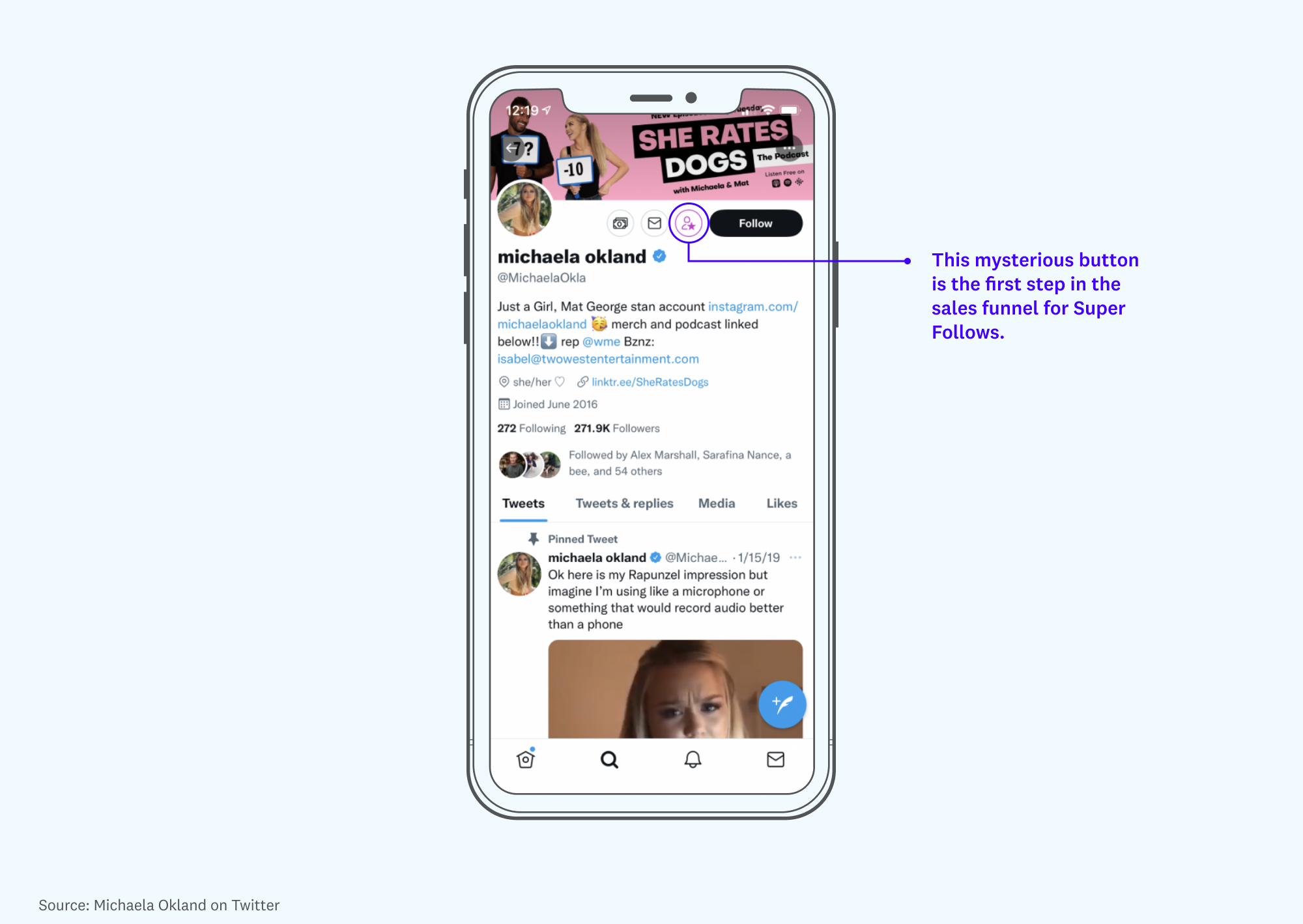

I outline the subscriber flow for Super Follows here, based on the funnel of Michaela Okland, a podcaster and prolific tweeter. As one of the original creators Twitter worked with to try out the feature, she made the most of her Super Follows potential. In fact, she generated more revenue from super followers than any other creator, according to that same SensorTower data snapshot two weeks post launch.

This is what Michaela’s profile looks like:

So far everything looks typical, other than the purple button to the left of the “Follow” button. It doesn’t say anywhere that this account has exclusive content for paid super followers, or pitch a paid-value proposition.

Maybe that’s fine, because we’re not even following this account yet; the target market for becoming a Super Follower is probably limited to people who already follow an account, so that makes sense.

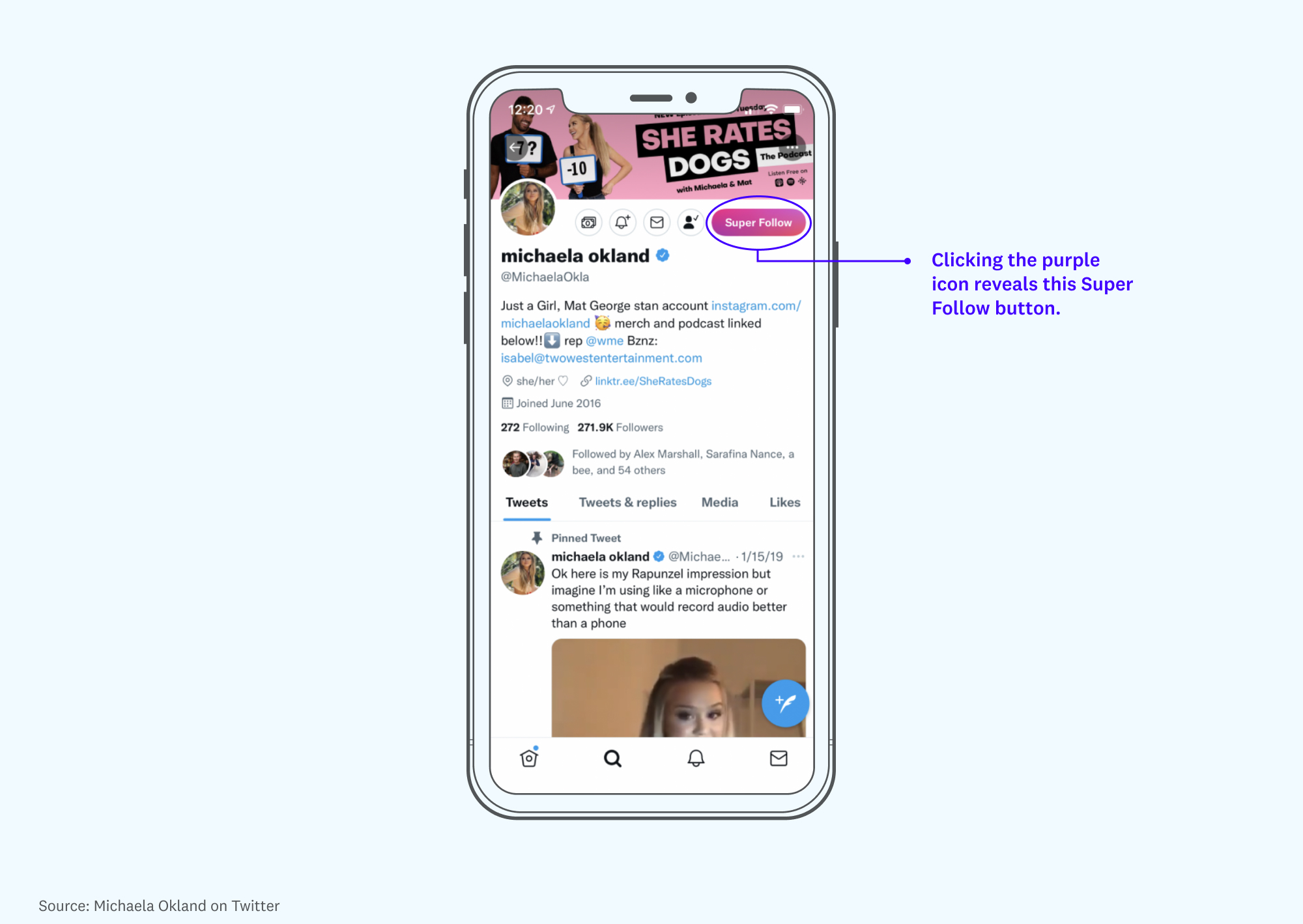

But let’s see what happens when we click the “Follow” button:

Now we see a bright pink “Super Follow” button. It’s eye-catching, but the “pitch” is conspicuously lacking. I just hit the follow button! It’s the exact moment when Twitter knows for sure I’m interested in content from this creator. Why not tell me what I am missing if I don’t pay? Why not sell me?

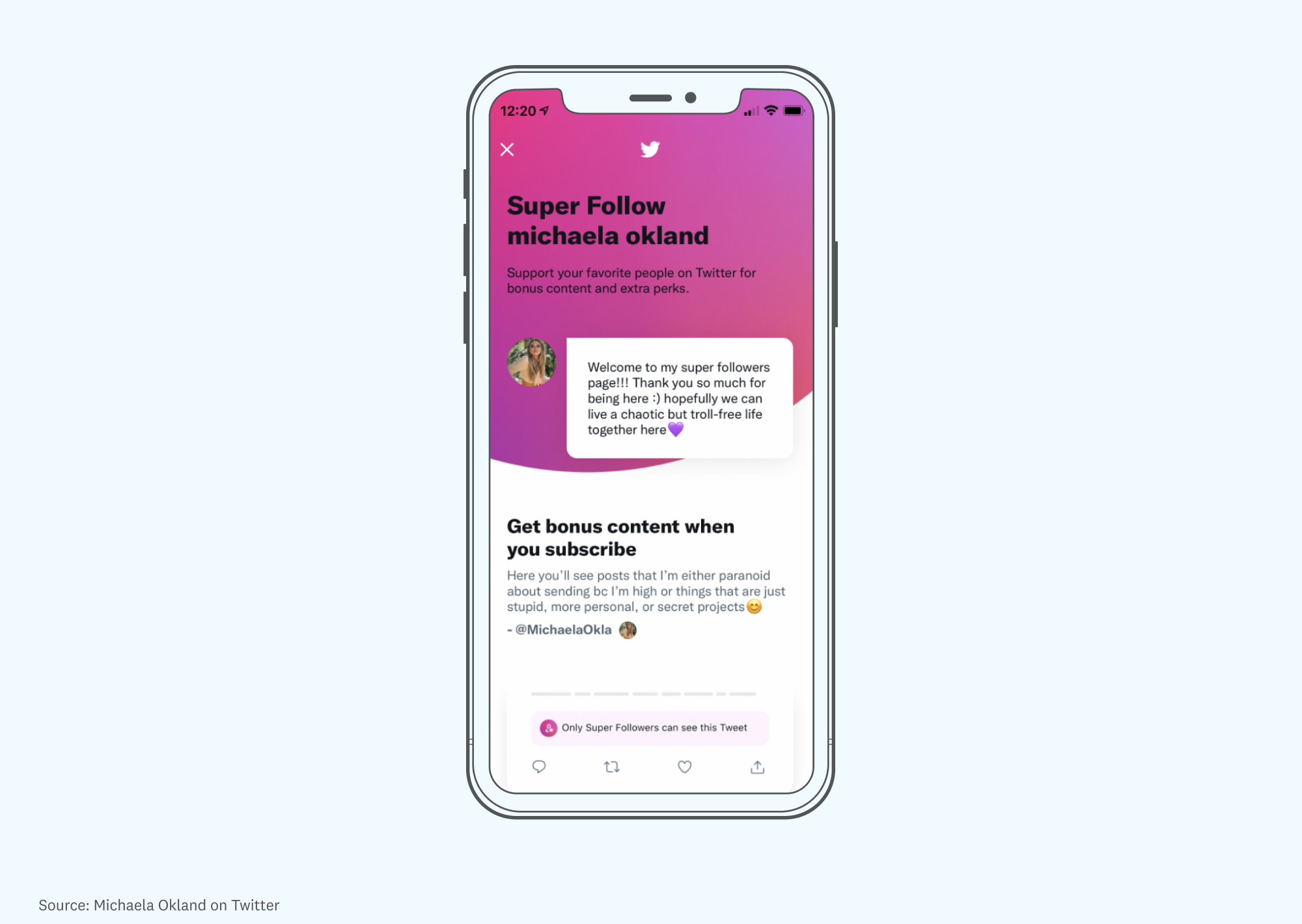

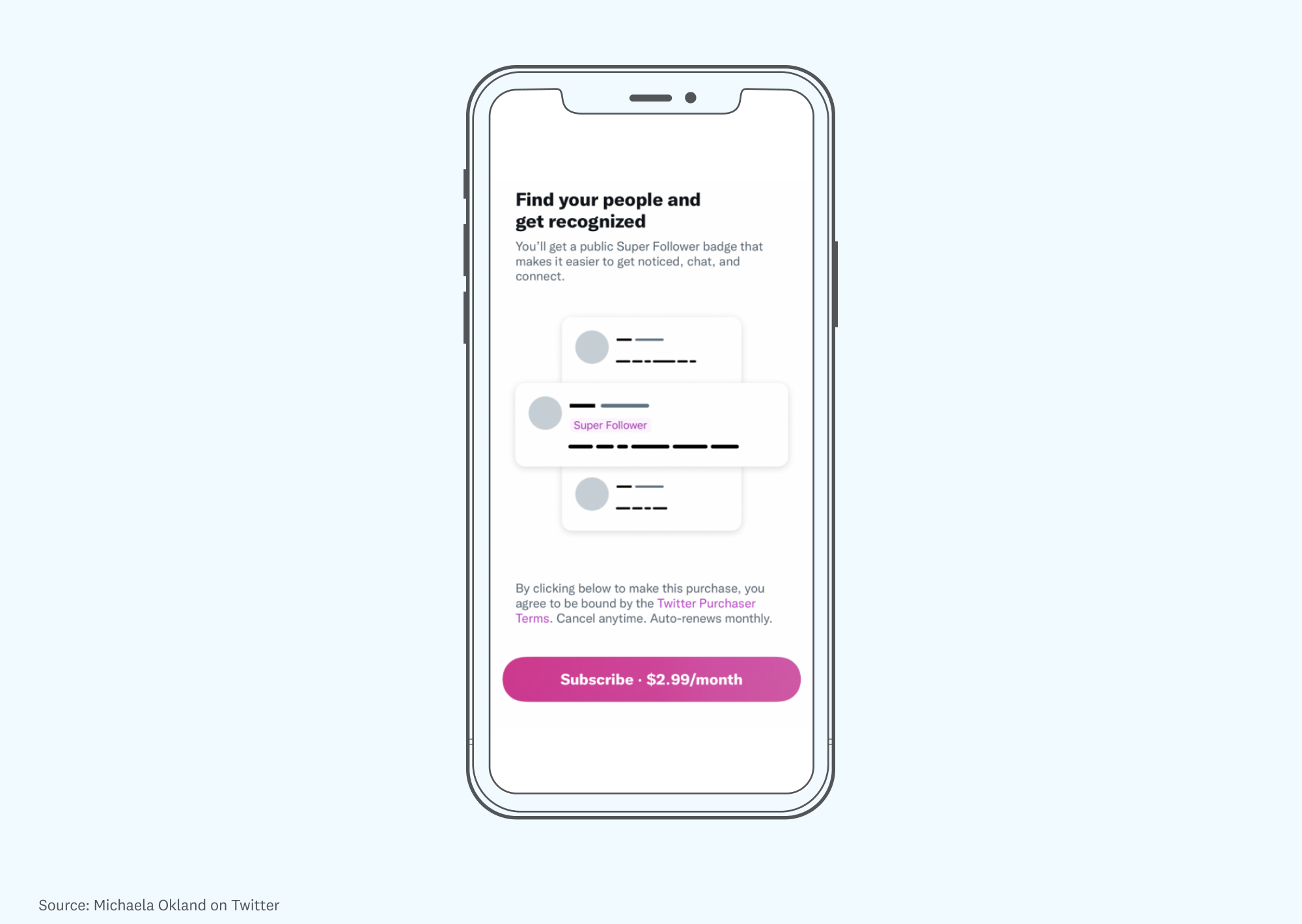

To get the pitch, I’ve got to tap the “Super Follow” button. Here’s what we see when we do:

The most fundamental trade-off every creator platform faces when designing such pages is persuading users to convert, without forcing creators to do too much work. You can tell Twitter leaned into the “making it easy for creators” side of that trade-off here: there appear to be just two short text fields that creators need to fill out. One is a general welcome statement at the top, and the second is a description of what kind of “bonus content” followers can expect.

If early results are any indication, this may not be enough! But Twitter is far from the only creator platform tackling this issue.

Sales funnel case study: YouTube payments

YouTube, which was acquired by Google in 2006 for $1.65 billion, has become a leading platform for video content, launching various features over the years to support video-native creators. Compared to Twitter, this is a more mature platform in the creator economy. But when it comes to payments, YouTube makes subscribing to creators harder than finding Waldo. Can you spot the button users have to click to pay creators?

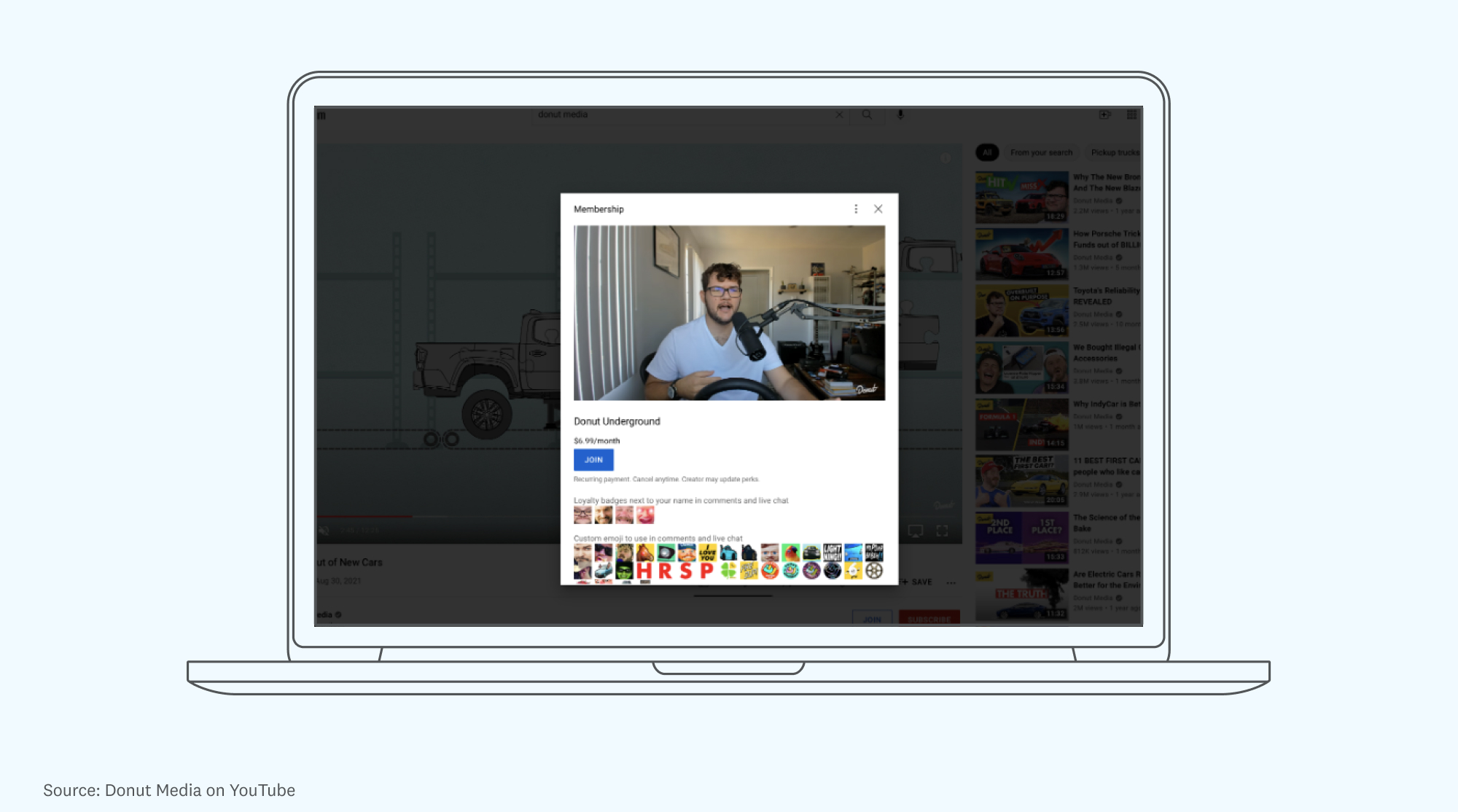

If you managed to find the “join” button, here’s what you’ll see:

Once you’ve joined, this is a pretty great interface! Video is the perfect format for YouTubers to make a persuasive pitch. It’s certainly high-effort when compared to a platform like Twitter, but that’s the right side of the trade-off for creator platforms to make: You’d rather raise the ceiling for the most dedicated creators than raise the floor for creators who will come and go without putting in much effort.

But though YouTube’s interface is visually effective, in cases such as these it’s beneficial to summarize the benefits of becoming a member, especially at the point that users are hovering over the “Join” button. In general, this provides a useful rule for any audio/video platform that wants users to get users to act: it’s crucial to have the pitch (and the “call to action” link) reinforced in text. Video and audio are both ephemeral, and it’s easy for the most important points of your message to get lost.

When I was Head of Product at Gimlet (the podcast network acquired by Spotify in 2018), we saw a much higher conversion rate on selling memberships when we paired the pitch in the audio with links and reinforced messaging in the show notes.

So, if Super Follows and YouTube Payments are examples of under-selling, how can platforms get it right?

The seemingly simple, surprisingly complex art of the sell

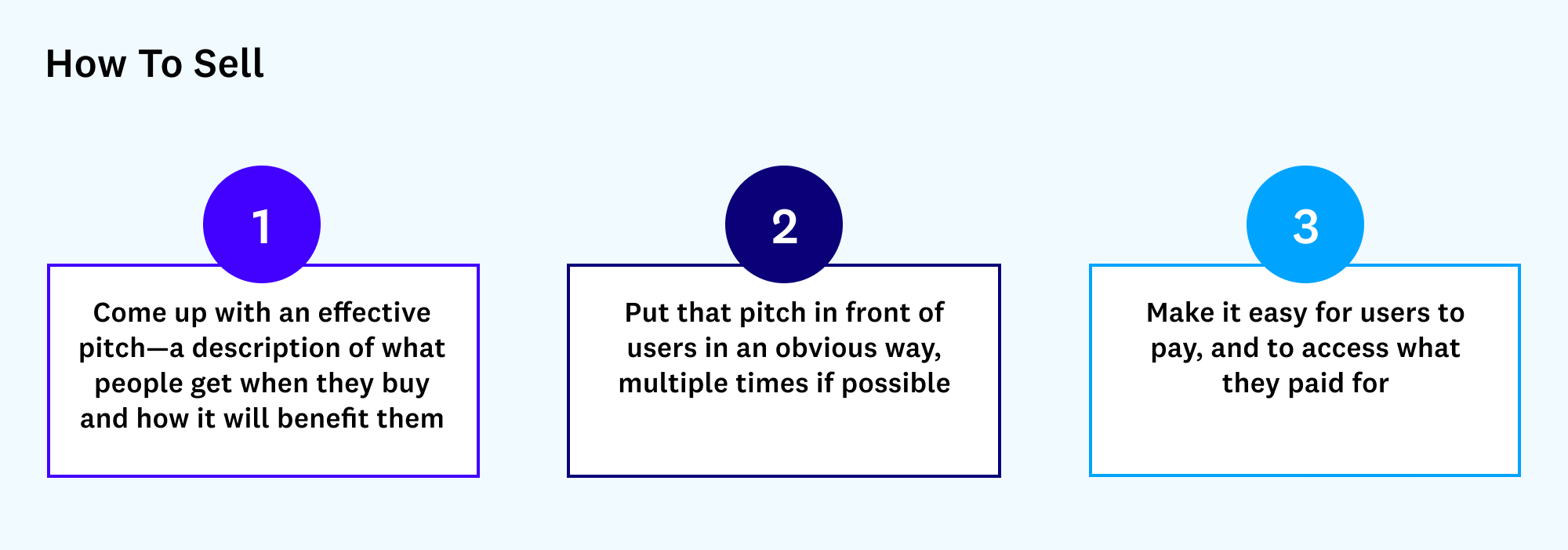

In my time helping creators sell subscriptions at Gimlet, Substack, and Every, I’ve come to understand there are three things that need to happen to acquire a new customer. They may seem simple, but effectively executing them can be tricky to nail:

While most platforms focus on that third step, as evidenced by the examples above, the first two requirements are more likely to be neglected. Here’s what it takes.

1. Understand your “genre” to hone your pitch

Crafting a pitch is surprisingly hard for creators, especially if they’ve already generated a slew of followers on a big platform with free content, like Instagram, TikTok, Twitter, or YouTube.

One strategy that works well in the Twitter case study, for example, is actively guiding creators toward specific value propositions that (in this case) the company feels will work best for most fans on its platform:

- Bonus content: See tweets that nobody else can see

- Community: Be seen by the creator and their fans

Based on the way Twitter’s subscribe page is designed, it looks like these value propositions were decided centrally by the company, rather than leaving all this text up to the user to create. This is a good thing.

Creator platforms should give users reasonable defaults and guidance, not only because it takes some of the work and risk out of creators’ hands, but also because, over time, it can reinforce what it means to become a Super Follower — or whatever the platform’s equivalent is — for fans. In theory, this reduces friction in the future because paid followers know what to expect.

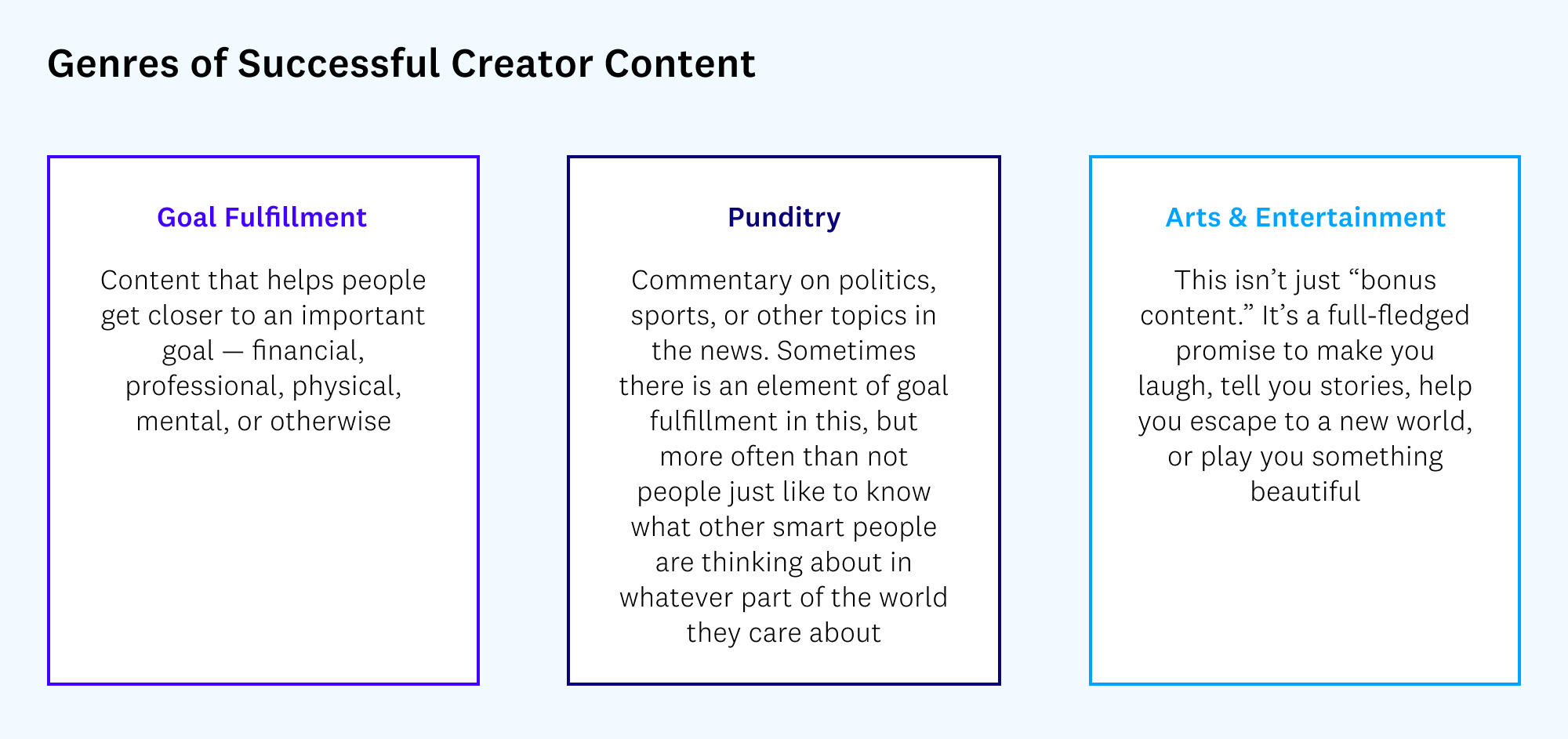

As time goes on and more creators launch paid content offerings, the types of messages that are likely to succeed often fall into one of a few buckets, or genres. As creators in book publishing, movies, magazines, newspapers, and TV learned what sells, they all developed their own familiar genres over time, along with conventions that signal to audiences what they can expect. The same process is happening on creator platforms now. Though it’s still early, there are a few emergent genres, from goal fulfillment to punditry to arts and entertainment.

These are some of the most popular emerging categories. Some creators straddle the line — this very post, for instance, bridges punditry (“what’s next for the creator economy”) and goal fulfillment (“how to generate more sales”). Of course, there are many different types of genres that are equally valid, and the taxonomies will continue to evolve.

What’s currently missing in the creator economy is often a close consideration of genre, and the implicit value propositions that users derive from it. In the traditional media world, you can look at a movie trailer for a comedy and easily understand the value proposition is that you’re going to have fun and laugh. You can walk into the business section of the bookstore and understand that all the covers in front of you basically promise different ways of succeeding professionally. With creator platforms, on the other hand, the pitch often begins at “support this creator” and ends with “get bonus content”; this doesn’t bolster the creator’s case or manage fans’ expectations.

As the friction to offer paid products lessens and more creators enter the fray, competition for consumer dollars will continue to intensify. So how do creators craft a good pitch, beyond simply understanding their genre?

The short, somewhat unsatisfying answer is that there is no infallible process; great pitches are surprisingly resistant to a one-size-fits-all formula. Generally speaking, however, it’s important to convey the basic elements of what you’re creating, what users will get out of it, how they can access it, how often it comes out, and how much it costs.

The best advice I have, based on what I’ve seen collaborating with dozens of creators on several platforms, is simple: pay attention to the details, be unique, and keep experimenting.

2. Put the pitch in front of users

This step is so simple, but so often neglected: fans have to actually encounter the pitch.

In my past experience as the VP of Product at Substack, and now as the cofounder of Every, I’ve noticed an obvious pattern to the moment when paid newsletters generate the most subscribers: It’s when the writer sends an email to free users that is primarily a pitch to become a subscriber. This could take the form of an announcement, a regular reminder, or a specific promotion. It can have a coupon, or announce an upcoming price increase — or not fiddle with the price at all! It could be tied to a specific post or could be a general solicitation. None of that seems to matter as much as the basic fact that you’re sending out an email with a list of reasons to subscribe, and a “Subscribe” button at the bottom.

Very few creator platforms seem to have learned this lesson. They’re all about a subtle upsell, with a small, tasteful button tucked neatly into some unobtrusive corner of the user interface. This is a missed opportunity: Platforms need to find elegant ways to cause fans to actually encounter pitches from creators.

One good example of this, which is also very new, is Twitter’s integration of Revue into their user profile pages.

It’s a breath of fresh air to see a platform that lets creators use prime real estate to make a direct pitch to their followers! As this example shows, the “sell” doesn’t need to be gaudy or annoying; it’s simply a way to alert people that this creator has a newsletter and removes the friction of signing up.

* * *

As platforms and creators become increasingly sophisticated at crafting and delivering pitches over time, the competition for fans’ dollars will become much more intense. In order to survive, creators will need to become ever more specialized, and the ecosystem of support tools and functions will continue to evolve to enable that specialization.

I believe that as this plays out, social media will increasingly begin to resemble traditional media: books, TV, film, magazines, games. Production value will increase, established genres will materialize, and dollars from fans will start flowing more freely. It’s inevitable — once creators and creator platforms stop neglecting the pitch and lean into the sell.