When learning to ride a motorcycle, you’re taught that where your eyes go, your bike goes. Look to your right and you’ll drift right. Look left, go left. There’s a lot of power in where you focus your attention.

That’s why nailing your North Star Metric(s) — the top-line metrics that all company priorities are aligned around — is so crucial. Whatever companies choose as their guiding metric, all energy and brainpower will flow in that direction. This can be hugely effective — it has worked wonders for companies like Airbnb, Netflix, and Uber, especially early on — but it can also be dangerous. By maintaining a laser focus on a single metric for too long, teams risk short-term thinking, missing new opportunities, and sacrificing the user experience. I share some data and case studies below to provide lessons for narrowing in on your own North Star Metric, knowing when to broaden your lens, and when to pivot your approach.

Broadly, there are six categories of North Star Metrics:

- Revenue (e.g. ARR, GMV):

The amount of money being generated — the focus of ~50% of companies. - Customer growth (e.g. paid users, marketshare):

The number of users who are paying — the focus of ~35% of companies. - Consumption growth (e.g. messages sent, nights booked):

The intensity of usage of your product, beyond simply visiting your site — the focus of ~30% of companies. - Engagement growth (e.g. MAU, DAU)

The number of users who are simply active in your product — the focus of ~30% of companies. - Growth efficiency (e.g. LTV/CAC, margins)

The efficiency at which you spend vs. make money — the focus of ~10% of companies. - User experience (e.g. NPS)

The measure of how enjoyable and easy to use customers find the product experience, overall — the focus of ~10% of companies.

So what are the optimal North Star Metric(s) for startups? I surveyed current and past employees at over 40 of today’s most successful growth-stage companies to compile the table below; the findings provide a helpful framework for organizations seeking their own guiding metrics.

A framework for choosing your North Star Metric

A framework for choosing your North Star Metric

The #1 question to start with: Which metric, if it were to increase today, would most accelerate my business’ flywheel? As you’ll see below, refining your ideal North Star Metric (NSM) — deciding which of the six categories above to focus on — depends heavily on your business model, how your product grows, and how your product is used.

Type of company: Marketplaces and platforms

Most common North Star Metric: Consumption growth

Marketplaces and platforms make money from usage — the more consumption they drive within their platforms, the faster they grow. Marketplaces that take a cut of each transaction, like Airbnb, Uber, Lyft, and Cameo, focus their NSM on the volume of transactions (nights booked, rides taken, and orders placed, respectively).

Platforms that instead charge a flat fee per usage, like the cloud communications platform Twilio and the fintech giant Plaid, spotlight activity: in this case, messages sent and bank accounts linked. At first glance, it may seem that concentrating on GMV would be the better choice in both of these cases, but as I’ll discuss below, a focus on revenue as a NSM can lead companies astray.

Type of company: Paid-growth driven businesses

Most common North Star Metric: Growth efficiency

When your business is driven by performance marketing, there are two common NSMs: margins and LTV/CAC. Businesses like the meal kit service Blue Apron, the ecommerce bedding company Casper, and telehealth startup Hims all fixate on optimizing margins because they ship a physical product with many layers of costs. The more they make per-unit, the faster they grow.

Meanwhile, companies that are purely digital and invest most of their budget into performance marketing, like the mediation and sleep app Calm, tend to zero in on LTV/CAC because most of their spend goes into digital ads. Some companies in this category also consider “payback period” their NSM in order to optimize how quickly they can reinvest in their growth.

Type of company: Freemium team-based B2B products

Most common North Star Metric: Engagement and/or customer growth

This category of products, which includes companies such as the collaborative online document startup Coda and Slack, grows through a bottom-up acquisition model. These businesses aim to hook free users who then invite their colleagues. Eventually, after businesses reach a certain level of usage, they upgrade to a paid plan.

Depending on the maturity of the business and how bottom-up driven their growth is at this stage, these companies either optimize for engagement (e.g. Coda uses “DAU14,” HubSpot uses “WAU”), paid customers (Airtable uses “Weekly Paid Seats” and Asana uses “Weekly Active Paid Users”), or paid teams (Slack uses “Number of Paid Teams,” while Dropbox uses “Teams using Dropbox Business”). The more mature and sales-driven the product is, the more companies focus on customers over engagement.

Type of company: UGC subscription-based products

Most common North Star Metric: Consumption

For select products that are driven by content creation, like Twitch and the video messaging platform Loom, it can be more effective to optimize consumption — say, five-minute plays, or videos created that are viewed — rather than engagement. This is because the sharing and consumption of content is at the heart of their growth flywheel.

Though consumption and engagement are similar metrics, the former is much more active — creating a video, for example, rather than merely visiting the site. Consumption is more likely to result in users sharing the content, thus driving the growth flywheel.

Type of company: Ad-driven businesses

Most common North Star Metric: Engagement

Every company that monetizes through web traffic (by running ads), such as Facebook, Pinterest, and Snap, opts for a North Star Metric based on engagement.

The question is whether one focuses on Daily Active Users (DAU), weekly (WAU), or monthly (MAU). Facebook and Snap target DAU because, for better or worse, social media is a daily habit for most. Meanwhile, Pinterest looks at WAU, since it doesn’t expect its users to need the product daily. And Spotify’s podcast business hones in on MAU, most likely because podcast listening is more sporadic for users.

Type of company: Consumer subscription products

Most common North Star Metric: Engagement or customer growth

Consumer subscription products such as the language learning app Duolingo, dating app Tinder, and the exercise tracking app Strava tend to choose either engagement or customer growth as their North Star Metric. Duolingo and Strava, for example, both focus on engagement (e.g. DAU and MAU, respectively) because they have a large free-user base that eventually migrates to paid; thus, the more engaged their free users are, the more they know they’ll add paid customers.

Alternatively, companies like Tinder, Spotify, and Webflow zero in on customer growth over engagement. Interestingly, Tinder concentrates on the percentage of paid accounts, rather than an absolute number. That’s because with so much natural churn — as people presumably find their soulmates — they are much better off if they can get early users to upgrade quickly. Patreon found that growing successful creators (by tracking the number of new creators making over a certain dollar amount) was the key to its early growth flywheel. Spotify, which has both a subscription business (music) and an ad-based business (podcasts), focuses on engagement, customer growth, and consumption.

Type of company: Products that differentiate on experience

Most common North Star Metric: User experience

Some products win or lose based purely on their user experience — how delightful, easy, and useful customers find the product. Thus, these types of companies include a quality-oriented North Star Metric.

While Robinhood and Superhuman rely on net promoter scores (NPS) — which reveal how likely a user is to recommend a product — Duolingo looks at a metric it calls “learning competency” using the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR), which is the international standard for measuring language ability. They do this because for their product experience, it makes sense to define language proficiency at different levels that match the user’s goals.

Other notable and unique North Star Metrics

While most companies fit within the six structures outlined above, some are not so neatly boxed in — their North Star Metrics are based on factors specific to their particular business model. Shopify, for example, focuses on growing customers (i.e. “active merchants”) rather than on consumption (the number of transactions). This is because rather than solely collecting a take-rate, the company also charges a subscription fee. Thus, they’re looking for long-term supply growth with lucrative recurring subscription revenue.

Patreon strives to drive awareness among potential users; breakout success stories are fuel for their growth. The platform uses a unique North Star Metric I’ll call activated supply, which translates to “number of creators making over a certain amount.” That’s most likely their key metric because these profitable creators drive their top-of-funnel growth.

Miro, the visual collaboration software, uses “number of collaborative boards” as its North Star Metric, which indicates that the core of its growth strategy is inter-organization virality.

Similarly, Amplitude, a B2B subscription product, focuses on “Weekly Learning Users” — users who consume and share more than three charts per week.

The popular consumer subscription business Netflix measures consumption in the form of “median view hours per month,” rather than measuring customer growth. The reason? Most likely they’ve found that the intensity of usage directly drives retention to their service.

There’s also an interesting distinction between focusing on paid users vs. active paid users as your North Star Metric. The project management software companies Asana and JIRA both spotlight weekly active paid users, while companies like Airtable and Slack simply focus on paid users. The difference, I suspect, is rooted in the recognition that inactive paid users will soon churn. Thus, there’s more power in tracking high-value paid users.

Using “jobs to be done” to determine your North Star Metric

An alternative approach to choosing your North Star Metric is to ask yourself: What jobs are our users hiring our product to do? The “jobs-to-be-done” framework (originally coined by Clayton Christensen) focuses on the task or progress your customer is trying to make in a given circumstance, and not just on “knowing your customer” or something similar. It’s a way of identifying the driver behind a given purchase or usage and optimizing for that in a way that your competitors can’t or won’t. In this case, the North Star Metric needs to measure what matters most when fulfilling the job to be done for the customer or user. For example:

Plaid’s job to be done: Link my bank account to an app I’m using

Thus, prioritize “bank accounts linked.”

Miro’s job to be done: Collaborate with colleagues remotely

Thus, target “collaborative boards” as a North Star Metric.

Twitch’s job to be done: Watch gamers play live

Thus, focus on “five-minute plays,” the number of users who have watched a stream for five consecutive minutes or more.

Lyft’s job to be done: Get a quick ride someplace

Thus, focus on “number of rides.”

So what about revenue as a North Star Metric?

Cash is king, the old mantra goes — and about half the startups I surveyed prioritize revenue as their North Star Metric. Some of this is about being able to dictate your own destiny as a venture-backed company. But is revenue the right North Star Metric?

Companies like Amplitude, Figma, Notion, Patreon, and Superhuman actively focus on revenue as a North Star Metric — be it ARR, GMV, or plain old revenue growth — while companies like Airbnb, Miro, Netflix, Tinder, and Spotify purposely avoid concentrating on revenue. The reasons for this include:

- It’s spiky, and thus hard to make operational. At Airbnb, for example, revenue was impacted by factors such as currency exchange rates, average lengths of stay, and host pricing decisions. But by honing in on a metric one level removed, such as “nights booked,” teams could better track the impact of their work more directly.

- Focusing on revenue goals too early can lead to suboptimal decisions, such as spending too much time optimizing pricing — or being afraid to lower pricing, for that matter — which can hurt your long-term business growth.

- A goal around revenue can be uninspiring to the team. People often join companies to accomplish a specific mission; rarely is that mission simply growth in generating revenue. Metrics that are one step removed, such as number of paid customers, are more motivating because teams can assume that a paid customer is finding value in the product, so the company (and thus the employee) is delivering value.

Of course, in the end everyone cares about revenue, but there are some good reasons to avoid making revenue growth your singular North Star Metric. Instead of concentrating exclusively on revenue as your north star, what’s another metric that is a leading indicator of revenue, one that is operationally easy to track and optimize?

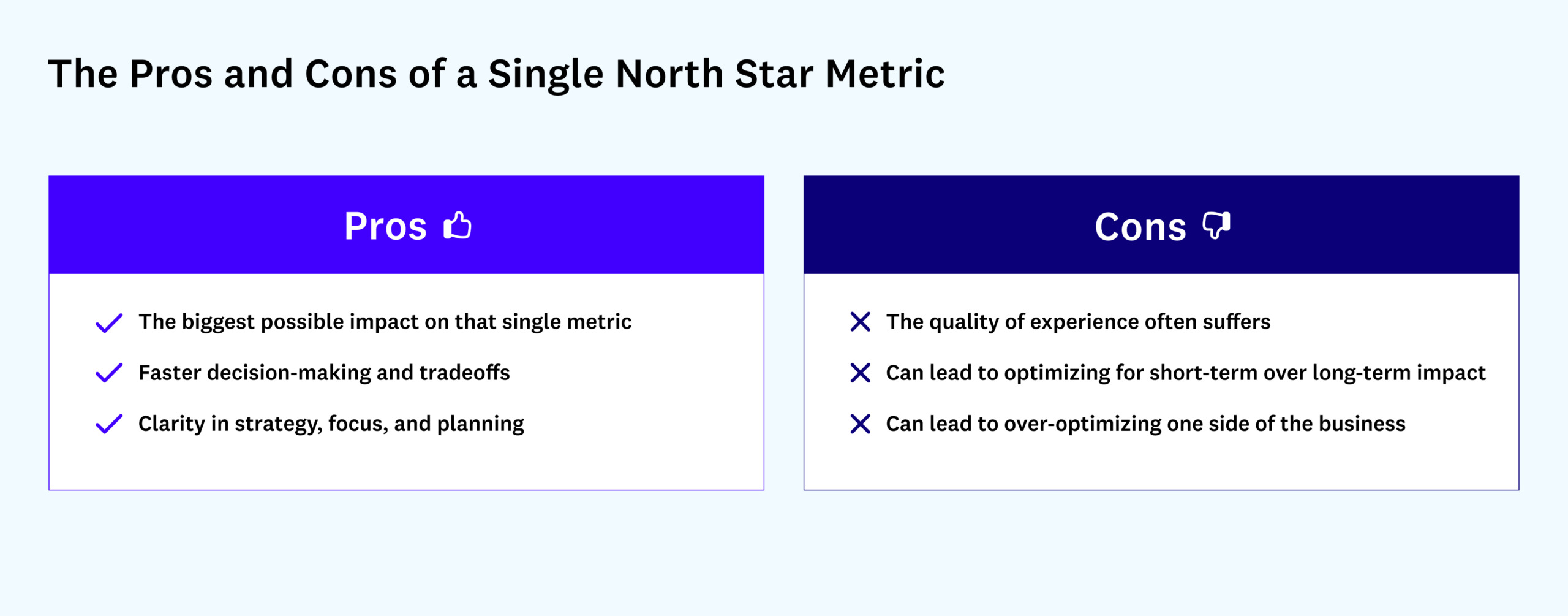

There’s typically only one North Star Metric

Some have cautioned against a single North Star Metric, arguing that you’re likely to over-rotate on one aspect of the business and constrain your growth. But the majority of companies continue to align around a sole metric (particularly if you exclude revenue) because it’s the best way to make a noticeable impact. Having that single focal point often leads to a more cohesive planning and decision-making strategy, company-wide.

Companies that do have multiple North Star Metrics typically only do so when they layer on a metric for quality (e.g. Superhuman, Slack, Duolingo), or when they have multiple products with different goals, like Spotify does with subscription music and paid podcasts, looking at both customers, engagement, and consumption.

To nail your output metrics, calibrate the input metrics

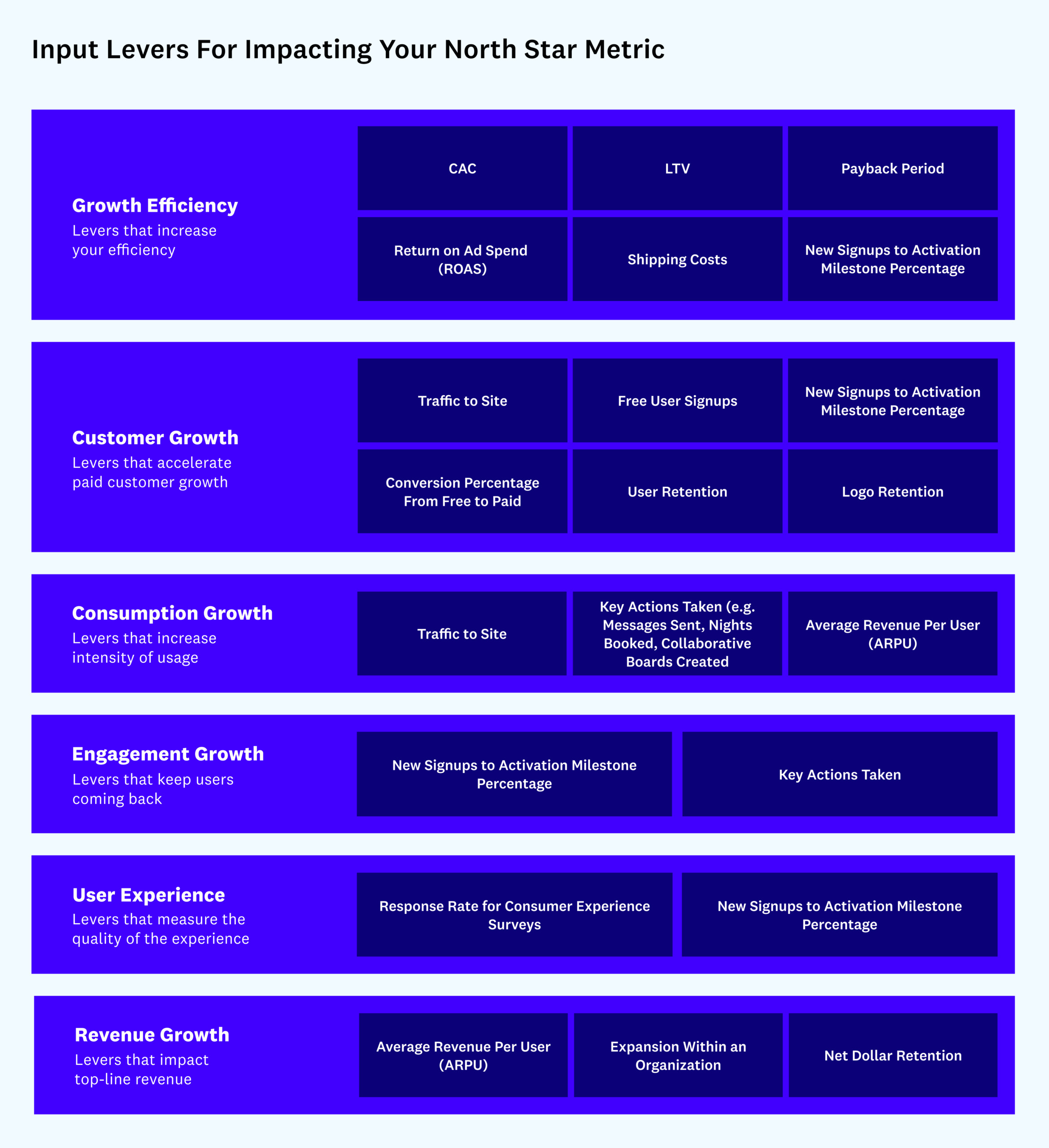

Rarely can you or your team directly or solely impact a North Star Metric, such as increasing active users or increasing revenue. Instead, these metrics are the output of the team’s day-to-day efforts, such as increasing the conversion of a flow, or driving more traffic to the site by running more Google ads. That’s why these are called output metrics and input metrics. Once you have your North Star Metric (an output), your next step is to break this metric down into its component parts and decide which metrics (the inputs) to invest in.

When I was at Airbnb, for example, our North Star Metric was “nights booked.” This isn’t a metric you can easily build a roadmap around because it’s too broad. Where do you even start coming up with ideas for how to increase the number of trips people book? Instead, we listed out the input metrics that feed into this higher-level metric. For example, if you increase the guest conversion rate, add more Airbnb homes, or boost the number of visitors to the site, you’ll increase the number of nights booked. With such granular and actionable input metrics, you can actually come up with concrete ideas and align teams around them as goals (e.g. “Add 10,000 new homes to the platform in Q1”). At the same time, the entire company still had a higher-level North Star, which each of these team efforts funnel into.

Whenever you have a candidate for your North Star Metric(s), determine what levers move this metric, and then focus your ideation around those input metrics. Here’s a (non-exhaustive) set of input metrics for each of the six types of North Star Metrics I outlined above:

* * *

The companies I surveyed in this post have all been around for many years. Even so, about a quarter of them told me that their North Star Metrics had recently changed, or were about to change. For example, Dropbox centered on engagement (MAU) early on, then shifted to a focus on paid customer growth as they transitioned their business model from B2C to B2B. Figma and Uber moved away from revenue as their NSM in order to double down on market share. Spotify set its sights on consumption once it introduced its podcasting business. Netflix has changed its NSM more times than people can count — originally it focused on the percentage of DVDs that arrived the next day in the mail, later on the percentage of members who watched at least 15 minutes of streaming in a month, and more recently, on median view hours per month.

The examples listed above are growth-stage companies. In the earliest stages of a company, however, before you’ve found the fabled product-market-fit, your singular aim should be answering one question: “Am I building something people want?” Instead of fixating on revenue or customer growth or MAU, I recommend you start by focusing on “cohort retention” — are enough people sticking after using your product? If you can’t get people to stick around, nothing else will matter in the end. (You can read more about retention here.)

Finally, no matter what stage you’re at as a startup or company with a new product line, expect your North Star Metric to change as your strategy shifts. It will evolve as you learn more about what keeps your team focused, motivated, and building toward the ultimate vision. Your North Star Metric is your strategy, and your strategy is your North Star Metric. Choose wisely.

Views expressed in “posts” (including articles, podcasts, videos, and social media) are those of the individuals quoted therein and are not necessarily the views of AH Capital Management, L.L.C. (“a16z”) or its respective affiliates. Certain information contained in here has been obtained from third-party sources, including from portfolio companies of funds managed by a16z. While taken from sources believed to be reliable, a16z has not independently verified such information and makes no representations about the enduring accuracy of the information or its appropriateness for a given situation.

This content is provided for informational purposes only, and should not be relied upon as legal, business, investment, or tax advice. You should consult your own advisers as to those matters. References to any securities or digital assets are for illustrative purposes only, and do not constitute an investment recommendation or offer to provide investment advisory services. Furthermore, this content is not directed at nor intended for use by any investors or prospective investors, and may not under any circumstances be relied upon when making a decision to invest in any fund managed by a16z. (An offering to invest in an a16z fund will be made only by the private placement memorandum, subscription agreement, and other relevant documentation of any such fund and should be read in their entirety.) Any investments or portfolio companies mentioned, referred to, or described are not representative of all investments in vehicles managed by a16z, and there can be no assurance that the investments will be profitable or that other investments made in the future will have similar characteristics or results. A list of investments made by funds managed by Andreessen Horowitz (excluding investments for which the issuer has not provided permission for a16z to disclose publicly as well as unannounced investments in publicly traded digital assets) is available at https://a16z.com/investments/.

Charts and graphs provided within are for informational purposes solely and should not be relied upon when making any investment decision. Past performance is not indicative of future results. The content speaks only as of the date indicated. Any projections, estimates, forecasts, targets, prospects, and/or opinions expressed in these materials are subject to change without notice and may differ or be contrary to opinions expressed by others. Please see https://a16z.com/disclosures for additional important information.