This is an edited version of a post that originally ran here.

For most queries, Google search is pretty underwhelming these days. Google is great at answering questions with an objective answer, like “# of billionaires in the world” or “What is the population of Iceland?” It’s pretty bad at answering questions that require judgment and context like “What do NFT collectors think about NFTs?”

The evidence is everywhere. These days, I find myself suppressing the garbage Internet by searching on Google for “Substack + future of learning” to find the best takes on education. We hack Twitter with the “what is the best” posts over and over again. When I’m researching a new product, I type “X item reddit” into Google. I find enormous value in small, niche, often forgotten sites like Spaghetti Directory.

There’s an emergence of tools like Notion, Airtable, and Readwise where people are aggregating content and resources, reviving the curated web. But at the moment these are mostly solo affairs — hidden in private or semi-private corners of the Internet, fragmented, poorly indexed, and unavailable for public use. We haven’t figured out how to make them multiplayer. In cases where we’ve made them public and collaborative — here is a great example — these projects are often short-lived and poorly maintained.

The stated mission of a company worth almost two trillion dollars is to “organize the world’s information” and yet the Internet remains poorly organized. Or, stated differently, in a world of infinite information, it’s no longer enough to organize the world’s information. It becomes important to organize the world’s trustworthy information.

How did we get here?

It’s hard to believe, but one of Google’s main problems, once it got going, was that there just wasn’t much to see online. Having a great search engine is useless if somebody types in “how to grow an herb garden” and the answer doesn’t exist online. With the advent of Google AdWords, it became profitable to put out low-quality content that passed as informative and filled Google’s search engine results. The end result is that the websites at the top of Google are not necessarily the highest-quality ones, but rather the ones that put the most effort into SEO. What started as a well-intentioned way to organize the world’s information has turned into a business focusing most of its resources on monetizing clicks to support advertisers, rather than focusing on delivering trusted search results for people.

The problem, now so drastically different from a decade ago, is not what to read/buy/eat/watch/etc., but figuring out the best thing to read/buy/eat/watch/etc. with my limited time and attention.

Audacious teams, like DuckDuckGo and Neeva, are trying to compete with Google head-on by building massive horizontal search engines. Rather than crawling and indexing things their own way, they sit on top of existing data sources and position themselves as privacy-focused alternatives to Google. But protection of privacy is not a compelling enough reason to leave Google. For the vast majority of people, allowing them to “control their own data” is not a selling point, especially if it requires paying for something they’re used to getting for free.

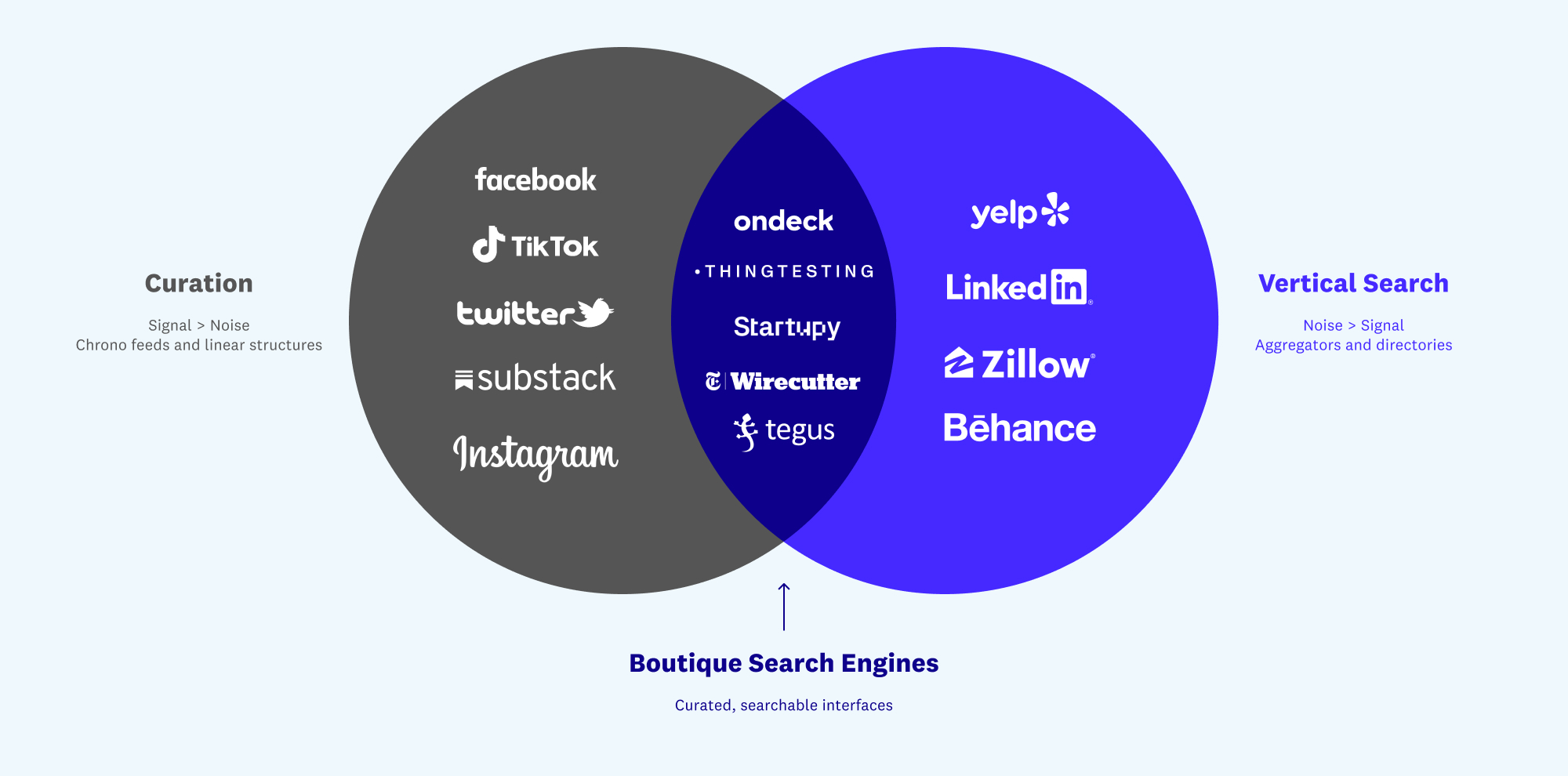

I believe the opportunity in search is not to attack Google head-on with a massive, one-size-fits-all horizontal aggregator, but instead to build boutique search engines that index, curate, and organize things in new ways.

Vertical search aggregators

Google is a great example of how the internet enabled scale and speed: every page on the web returned in an instant. But, increasingly, we’re seeing that this scale is at odds with a fundamental human need: relevance. Someone who wants to find the best freelance designer, or the best sushi restaurant, or the best NFT to buy will not find the answer on Google.

There is no search architecture that will work universally across all categories. It’s hard to imagine wanting to use the same UX to search for recipes as to search for freelancers. Whereas Google’s product begins and ends with a search bar, trading off functionality for simplicity, vertical search players like Yelp, Expedia, Zillow, and Behance emerged to fill functionality and relevancy gaps using structured data specific to their industries. With strong opinions on how to organize information, reflected in their choice of filters, vertical search aggregators have distinct advantages that horizontal software can never achieve.

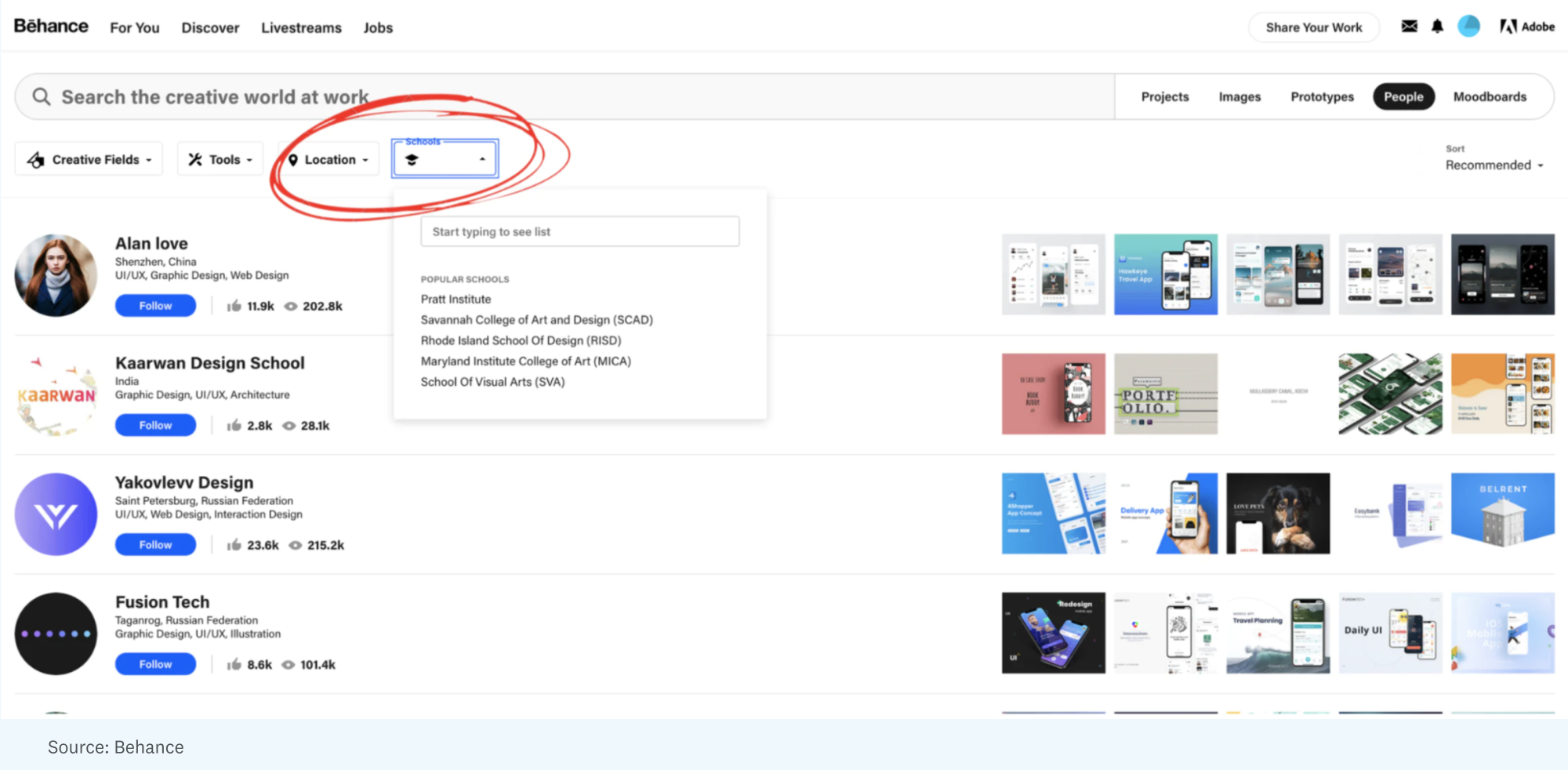

But here, too, relevance depends on the sociology of the current moment. For example, on Behance, the online creative community, school and location are featured prominently as filters — implying that where you live and where you went to school is an important indicator of the quality of your design portfolio. In a world where talent is being decoupled from credentialism and geography, those filters are losing relevance.

As signals evolve, new ways of indexing and surface areas for innovation emerge. If Behance were designed today, I’d argue neither “location” nor “school” would be filters.

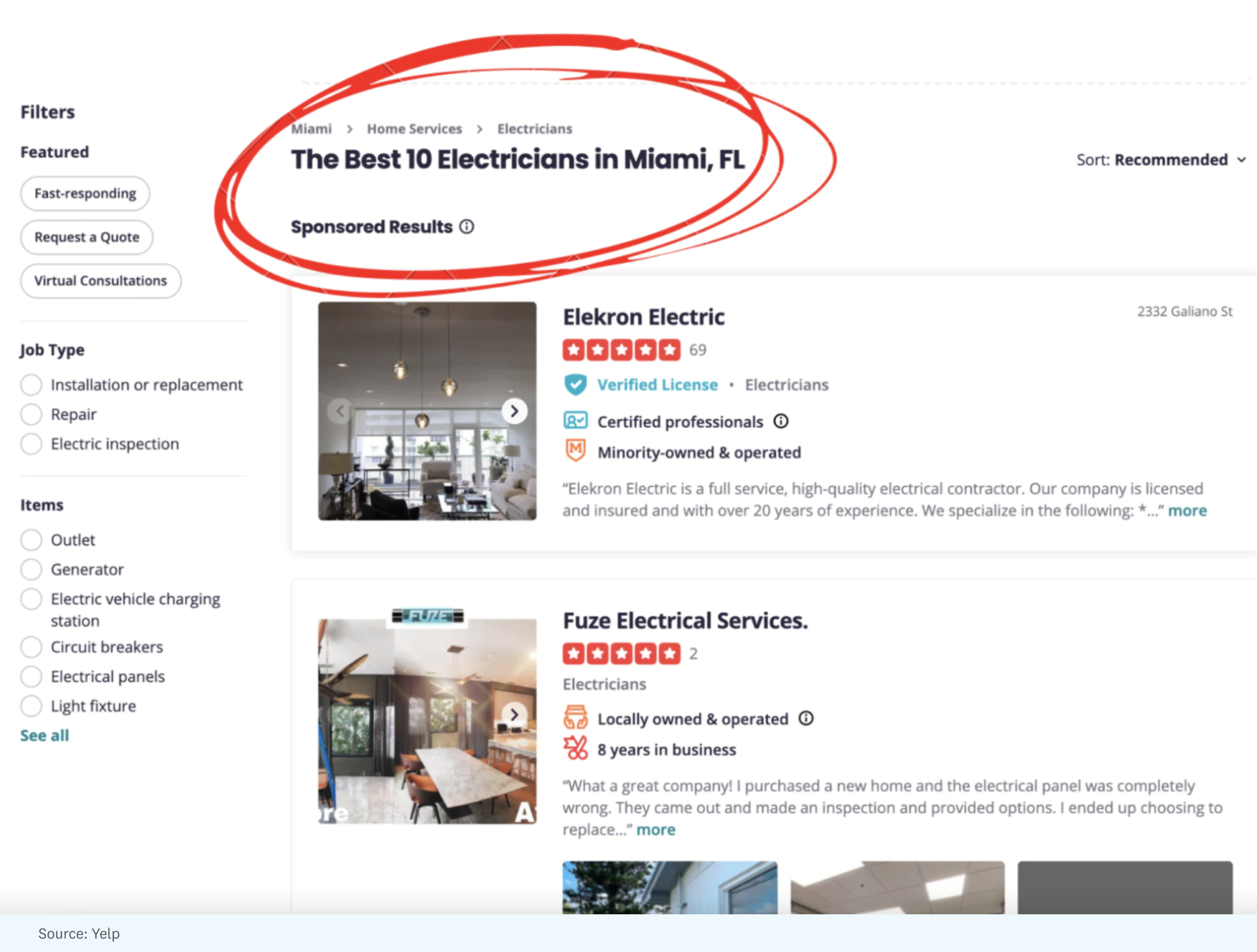

On Yelp, a search for “electricians in Miami” begins with a page titled “The Best 10 Electricians in Miami, FL” with text underneath that indicates the majority of these are sponsored results.

When you monetize via ads, curation takes a backseat to featuring advertisers because there is just less digital real estate available to curate your own recommendations. So these platforms end up making ethically dubious design choices that generate massive trust gaps.

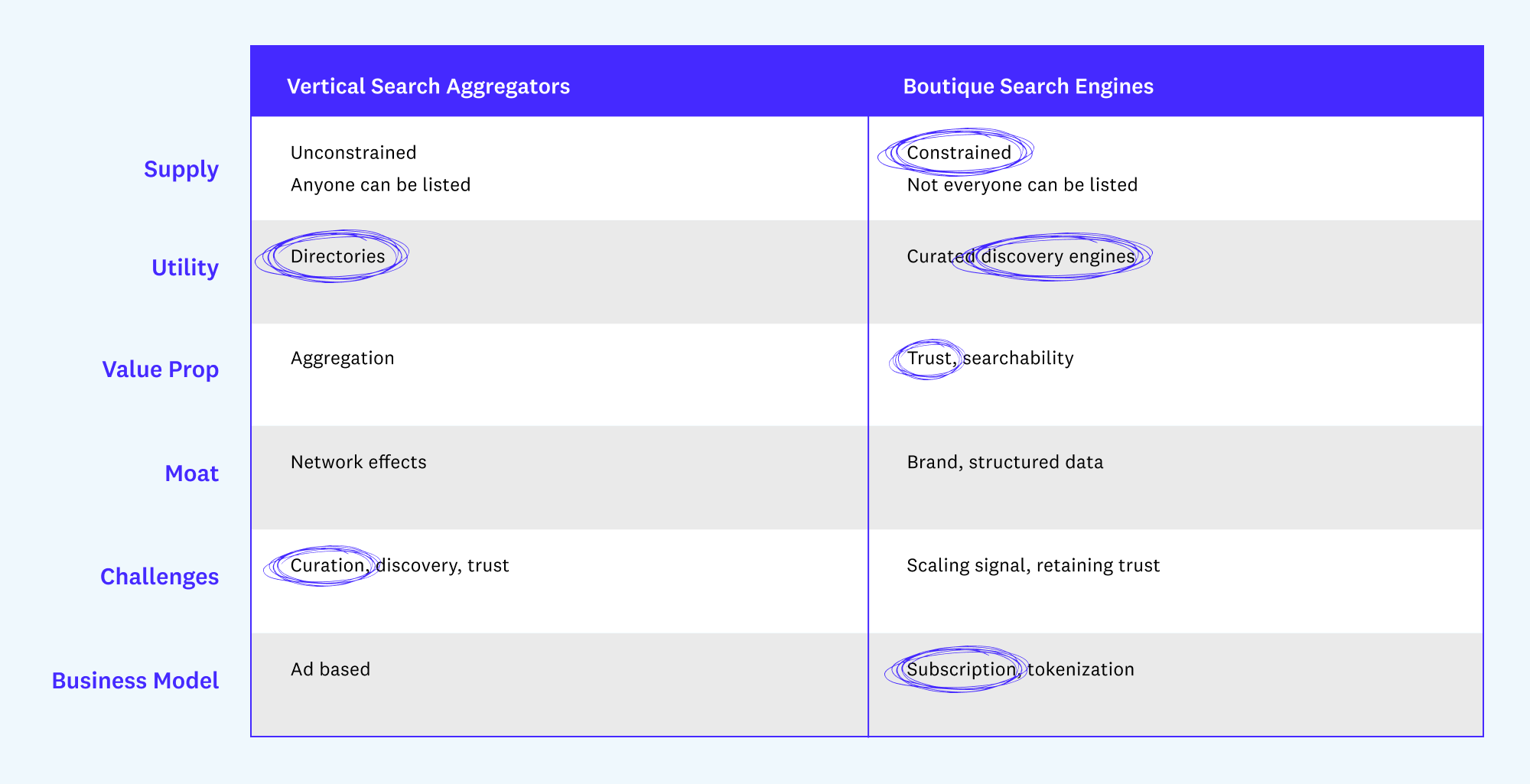

Additionally, across vertical search aggregators like Yelp, Zillow, LinkedIn, and Behance, anyone can have a profile. A combination of irrelevant filters, ad-based business models, and unconstrained supply has overwhelmed consumers and made it hard to find signals in these platforms.

Vertical search aggregators work when you know exactly what you want. But knowing what you want isn’t usually the starting point, which creates an opportunity to help the overwhelmed consumer with better discovery and curation along the funnel.

Curators, curators

It has become popular to say we live in the information age, and we need “curation” to help us sort through the mess. But thus far, the conversation around curation has been too focused on the content and not enough on the structure. We seem to have accepted the job of the curator as providing a product review, a list of links, or a song recommendation — all inside linear structures and chronological feeds designed to surface the ideas of the last 24 hours, not to accumulate and surface knowledge as needed.

A daily email with the top five Alibaba products feels fun and gimmicky as a side project, but it doesn’t help when you’re trying to find the best crib for your baby. Inevitably, you’ll want a way to search through a curator’s archives.

Curation, when thought of in the context of sharing bite-sized, isolated bits in feed-like architectures, is predominantly about entertainment, not utility. It’s not wrong to say there is a market for this kind of curation. What people miss, though, is that this market is already captured by Twitter, Facebook, and TikTok.

These entertainment giants offer curation that demands our attention, but they don’t offer curation on demand. The opportunity is in moving curated content feeds away from their never-ending-now orientation and toward more goal-oriented interfaces. People should be able to find whatever content they want on their terms and not be beholden to when the curator decides to publish.

Boutique search engines are next-level curation

All curation grows until it requires search, and all search grows until it requires curation.

—Ben Evans

Applying Ben Evans’ framework, it becomes clear that while the vertical search players have become too large and need curation, the curation feeds have become too long to browse and require search and structured data. The solution is better search and better curation, all wrapped in a better business model — a combination I call boutique search engines.

Searchable, curated interfaces will help us move away from ephemeral, time-bound feeds into contextual, high-signal, trustworthy knowledge spaces. Because searchable interfaces are densely linked, an explorer can follow multiple trails through the content, rather than being dumped into a “most recent” feed.

With such a tight relationship between curation and search, the real question is not whether you need curation or search but at what point it comes in, and how:

- Spotify doesn’t curate what songs make it to their platform. Instead, it takes the entire universe of music and finds endless ways to discover and search across its library, including a mix of manual curation (via playlists curated by its in-house team of curators and its users) and algorithms (like Discover Weekly).

- Wirecutter does not review every product. It manually curates the top products, and then uses search and other discovery tools to help you find what you need.

- Thingtesting is not automatically scraping all Consumer Packaged Goods brands on the Internet. Someone from its team or community went out of their way to add a brand to the database.

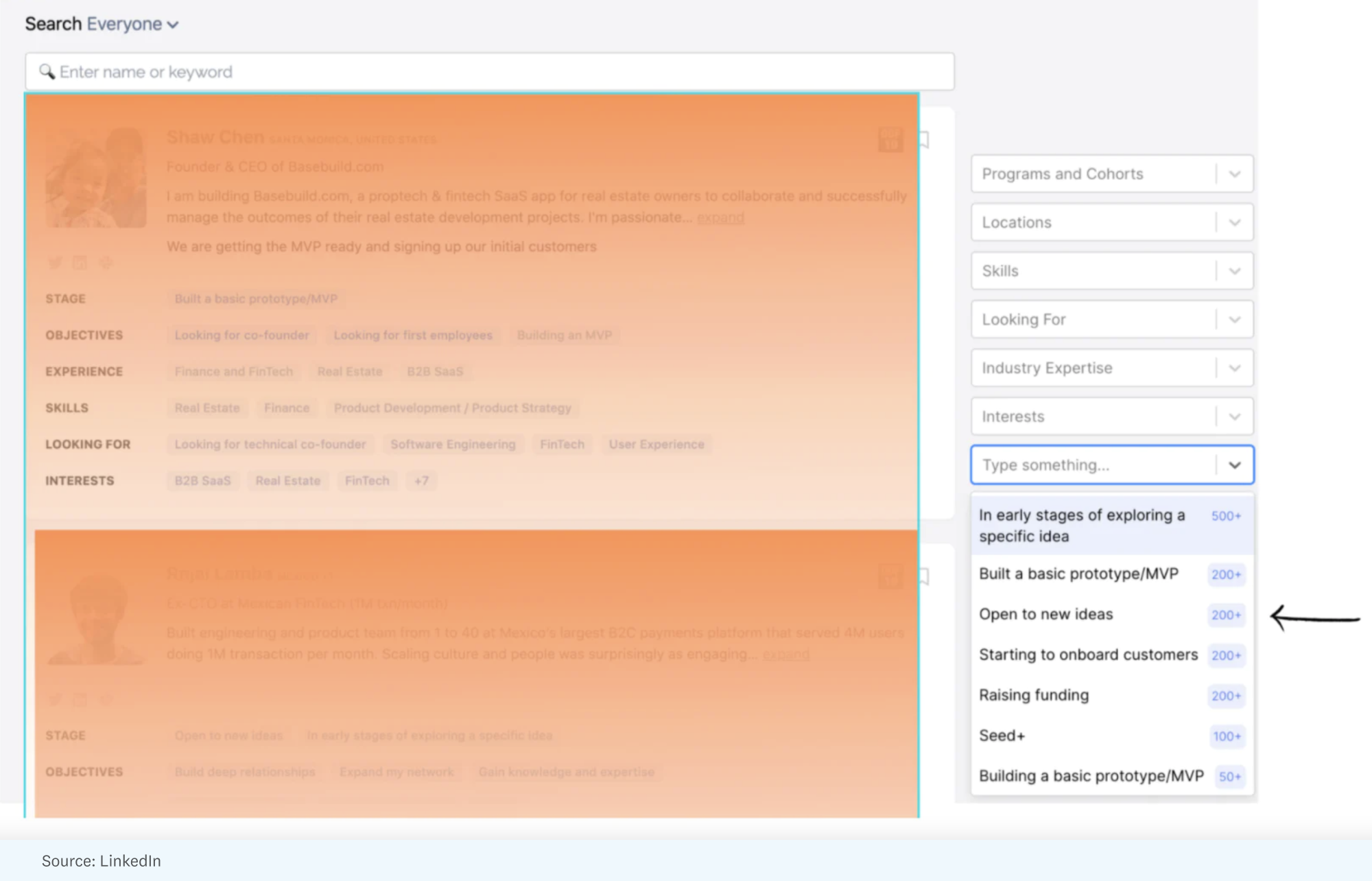

- If you’re searching the On Deck member database, you know everyone has applied, been vetted, and paid a fee to participate in the program.

- If you’re reading through transcripts on Tegus, you know the content comes from experts that have been handpicked by its team.

Across all these examples, the value is in what they exclude as much as what they include. The friction in the supply side is what generates the signal.

On top of the signals, these businesses have built strong search engines. OnDeck, for instance, has built an opinionated graph that allows you to discover talent in unique ways. For example, you can filter by people with “software engineering” skills whose current status is “open to new ideas.” As a founder looking for engineering talent, I’ll take this curated dataset over LinkedIn’s any day.

Unlike vertical search aggregators, boutique search engines feel less like the Yellow Pages and more like texting your friends to ask for a recommendation. They have constrained supply, which is the foundation for their biggest moat: trust. Importantly, boutique search engines also introduce new business models that don’t rely on advertising.

Questions remain, because search is hard

Building boutique search engines requires countless nuanced product choices. Getting the right mix of curation, search, algorithms, and business model will likely prove massively difficult and massively valuable. Here’s a non-exhaustive list of questions we’re pondering as we build Startupy, our attempt at a boutique search engine for qualitative insights.

If the value proposition is signal over noise, how do you scale the signal?

Over and over again, curation sites fall into an existential trap. They start with high-quality, curated recommendations. As they grow, they scale with crowdsourcing, often filling the gap with scraping. Over time, the content goes from great to good. At that point, vertical search aggregators like Yelp offer more utility. Yahoo, for example, became too big to be browsed, lost its signaling power, and reached the point where Google was better. The line between curator, compiler, and cataloguer is thin and there is a natural invisible asymptote — diminishing returns on more data over time.

What is the business model for this new wave of search engines?

On the surface, vertical search engines are simple — content is the supply, and eyeballs are the demand. But the last wave of vertical search engines was built atop ad-based business models, which made things trickier. In an ad-driven marketplace, the eyeballs are on the supply side. Their attention is what the demand side — advertisers — want. The downside to this ad-driven model is that advertisers and content producers are competing for the same attention, which is why these sites end up feeling like marketing blogs.

This is why subscriptions present an opportunity. Subscription simplifies the network effects to two sides: content as supply, a paying audience as demand. But subscription itself is not a panacea, especially when the use cases are not frequent enough. How often are you needing to find a freelancer? An investor? If use cases are not frequent enough, the utility of a search engine won’t translate to a sustainable business model and you’ll have to come up with your own flavor of “come for the search, stay for something else.”

Moreover, as my friend Joey points out in this article, any product where you’re spending a lot of time using it in incognito mode has a pretty big UX problem. How many New York Times accounts did you create before finally giving in to the paywall? With today’s subscription models, customers have no real incentive to help the platform grow. Nascent token-based business models show early signs of promise. By giving ownership to stakeholders and allowing subscribers to benefit from future upside, startups can overcome the cold start problem.

Though appealing, a playbook for tokenized business models has not yet emerged. I suspect this will change in the coming years, and I’m excited to improve my understanding of the subject.

Who curates the curators?

Platforms like Twitter delegate this responsibility to their users, who have to go through a long and arduous process of following a huge number of people to ultimately arrive at a self-curated timeline that mimics their interests. Some centralize their curation — at OnDeck, you trust that they are doing the work of selecting who can join their network. Yet others stay away from curation in favor of more traditional crowdsourcing. The spectrum is wide.

How do you find the search engine in the first place?

I started this piece arguing that Google needs to be unbundled. That’s a catchy headline but, in truth, I believe that until you can build habitual recall into your product, Google will be an important part of how your engine gets discovered in the first place. Zillow and Airbnb are examples of search companies that enjoy a good amount of direct traffic, but SEO was a big part of their early strategy. By being among the first to create the definitive page for a home, they benefited from an SEO land grab that has been hard to displace since.

We are far from achieving the grand vision of the Internet. The project of human knowledge, as it stands today, is a vast ocean of ephemeral and fragmented information and ideas, with the best sources near-impossible to find. We need more interfaces with a point of view on what information is missing, how it needs to be organized, and at what point of the value chain the curation has to happen.

Views expressed in “posts” (including articles, podcasts, videos, and social media) are those of the individuals quoted therein and are not necessarily the views of AH Capital Management, L.L.C. (“a16z”) or its respective affiliates. Certain information contained in here has been obtained from third-party sources, including from portfolio companies of funds managed by a16z. While taken from sources believed to be reliable, a16z has not independently verified such information and makes no representations about the enduring accuracy of the information or its appropriateness for a given situation.

This content is provided for informational purposes only, and should not be relied upon as legal, business, investment, or tax advice. You should consult your own advisers as to those matters. References to any securities or digital assets are for illustrative purposes only, and do not constitute an investment recommendation or offer to provide investment advisory services. Furthermore, this content is not directed at nor intended for use by any investors or prospective investors, and may not under any circumstances be relied upon when making a decision to invest in any fund managed by a16z. (An offering to invest in an a16z fund will be made only by the private placement memorandum, subscription agreement, and other relevant documentation of any such fund and should be read in their entirety.) Any investments or portfolio companies mentioned, referred to, or described are not representative of all investments in vehicles managed by a16z, and there can be no assurance that the investments will be profitable or that other investments made in the future will have similar characteristics or results. A list of investments made by funds managed by Andreessen Horowitz (excluding investments for which the issuer has not provided permission for a16z to disclose publicly as well as unannounced investments in publicly traded digital assets) is available at https://a16z.com/investments/.

Charts and graphs provided within are for informational purposes solely and should not be relied upon when making any investment decision. Past performance is not indicative of future results. The content speaks only as of the date indicated. Any projections, estimates, forecasts, targets, prospects, and/or opinions expressed in these materials are subject to change without notice and may differ or be contrary to opinions expressed by others. Please see https://a16z.com/disclosures for additional important information.