[1] E.g.,California Bankers Ass’n v. Shultz, 416 U.S. 21 (1974).

[2]See § 80603 (amending 26 U.S.C. § 6045(a)).

[3] United States v. Miller, 425 U.S. 435, 444 (1976).

[4] Branzburg v. Hayes, 408 U.S. 665, 688 (1972).

[5] Clark v. Martinez, 543 U.S. 371, 381 (2005).

[6] Cf. Peter Van Valkenburgh, Electronic Cash, Decentralized Exchange, and the Constitution (“In effect, the regulator would be ordering these developers to alter the protocols and smart contract software they publish such that users must supply identifying information to some third party on the network in order to participate . . . .”).

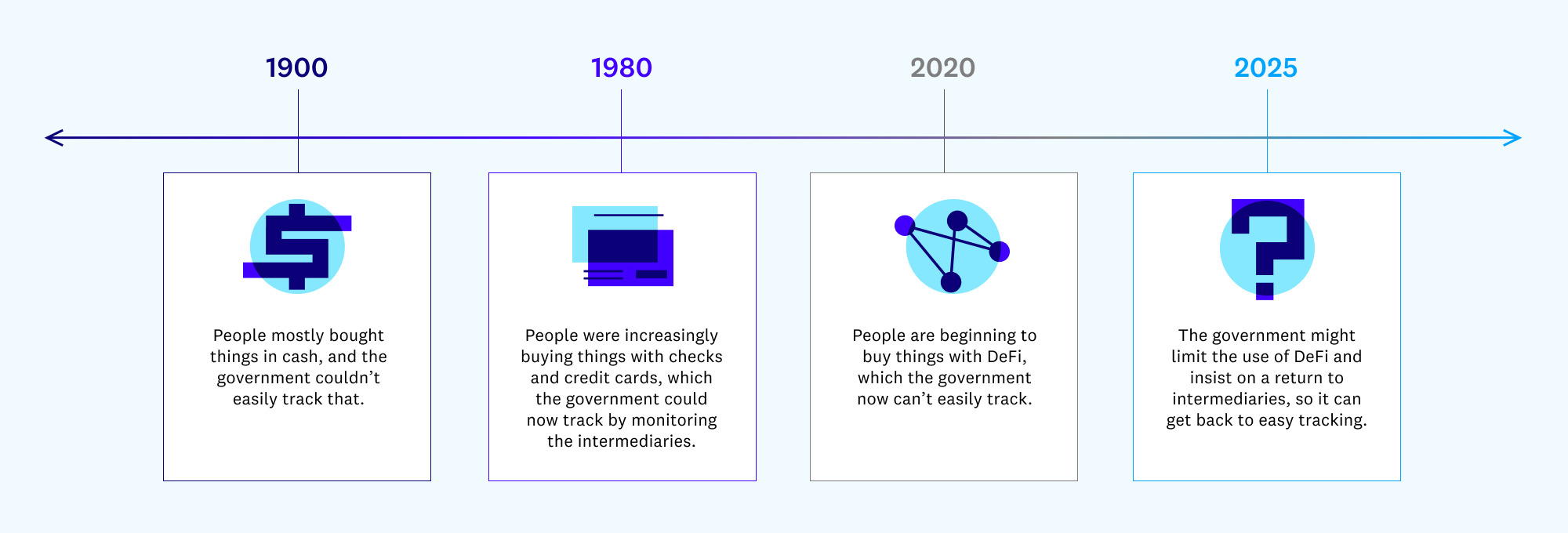

[7] This would be analogous to the government’s periodic attempts to limit the use of encryption. In the 1990s, the government sought to implement (and perhaps eventually mandate) the “Clipper chip”: a device that allowed encrypted communication, but required the encryption keys to be “escrowed” in some place where the government could then access them. More recently, in the late 2010s, federal law enforcement officials called for technology companies to implement similar key escrow facilities, so that (for instance) the government would always be able to unlock the data in your cell phone (assuming law enforcement got a warrant or a similar judicial authorization). This was referred to as the “going dark” debate: law enforcement was concerned that encryption could allow criminals and terrorists to entirely defeat the government’s surveillance and search techniques. See Rianna Pfefferkorn, The Risks of “Responsible Encryption”, Ctr. for Internet & Soc’y paper (Feb. 2018)

But at least the Clipper chip and key escrow facilities appeared to contemplate that the government could use escrowed information only with a warrant based on probable cause — trying to ban DeFi in order to make sure that financial transactions are routinely reported to the government would be a means to avoid the warrant and probable cause requirement.

[8] Smith v. Maryland, 422 U.S. 735, 744 (1979) (emphasis added); see also United States v. Miller, 425 U.S. 435, 442 (1976) (holding that people “lack . . . any legitimate expectation of privacy concerning the information kept in bank records” because they “contain only information voluntarily conveyed to the banks”); id. (stressing that “[t]he depositor takes the risk, in revealing his affairs to another, that the information will be conveyed by that person to the Government”).

[9] Cf. Peter Van Valkenburgh, Electronic Cash, Decentralized Exchange, and the Constitution (“If users do not voluntarily hand this information to a third party because no third party is necessary to accomplish their transactions or exchanges, then they logically retain a reasonable expectation of privacy over their personal records and a warrant would be required for law enforcement to obtain those records.”).

[10] United States v. Flores-Lopez, 670 F.3d 803, 807 (7th Cir. 2012); United States v. Wurie, 728 F.3d 1, 16 (1st Cir. 2013).

[11] Restrictions on overly tinted windows may be constitutional, but they are justified by the need “to ensure a necessary degree of transparency in motor vehicle windows for driver visibility,” Klarfeld v. State, 142 Cal. App. 3d 541, 545 (1983) (quoting 49 C.F.R. § 571.205 S2 (1982)); People v. Niebauer, 214 Cal. App. 3d 1278, 1290 (1989) (noting that certain levels of tinting are “permitted on certain windows not required for driver visibility”).

[12] McCarthy v. Arnstein, 266 U.S. 34, 40 (1924); cf. Guinn v. United States, 238 U.S. 347, 360, 364-65 (1915) (striking down a grandfather clause that was a clear attempt to evade the Fifteenth Amendment’s ban on discrimination based on race in voting qualifications); State v. Morris, 42 Ohio St. 2d 307, 322 (1975) (holding that private searches are not covered by the Fourth Amendment, unless they are orchestrated by the government “with[] intent to evade constitutional protections”).

[13] Fields v. City of Philadelphia, 862 F.3d 353 (3d Cir. 2017); Turner v. Lieutenant Driver, 848 F.3d 678 (5th Cir. 2017); ACLU of Illinois v. Alvarez, 679 F.3d 583 (7th Cir. 2012); Glik v. Cunniffe, 655 F.3d 78, 82 (1st Cir. 2011); Smith v. City of Cumming, 212 F.3d 1332 (11th Cir. 2000); Fordyce v. City of Seattle, 55 F.3d 436 (9th Cir. 1995).

[14] Fields, 862 F.3d at 359.

[15] Id.

[16] Carey v. Population Servs. Int’l, 431 U.S. 678, 685 (1977).

[17] See American Knights of the KKK v. City of Goshen, 50 F. Supp. 2d 835, 839 (N.D. Ind. 1999); Ghafari v. Municipal Court, 87 Cal. App. 3d 255, 261 (1979) (challenge brought by protesters who opposed the Iranian government); Aryan v. Mackey, 462 F. Supp. 90, 92 (N.D. Text. 1979) (likewise).

[18] See Church of American Knights of the KKK v. Kerik, 356 F.3d 197, 208-09 (2d Cir. 2004); State v. Berrill, 474 S.E.2d 508, 515 (W. Va. 1996); State v. Miller, 398 S.E.2d 547, 553 (Ga. 1990).

[19] See supra note 5 and accompanying text.

***

The views expressed here are those of the individual AH Capital Management, L.L.C. (“a16z”) personnel quoted and are not the views of a16z or its affiliates. Certain information contained in here has been obtained from third-party sources, including from portfolio companies of funds managed by a16z. While taken from sources believed to be reliable, a16z has not independently verified such information and makes no representations about the current or enduring accuracy of the information or its appropriateness for a given situation. In addition, this content may include third-party advertisements; a16z has not reviewed such advertisements and does not endorse any advertising content contained therein.

This content is provided for informational purposes only, and should not be relied upon as legal, business, investment, or tax advice. You should consult your own advisers as to those matters. References to any securities or digital assets are for illustrative purposes only, and do not constitute an investment recommendation or offer to provide investment advisory services. Furthermore, this content is not directed at nor intended for use by any investors or prospective investors, and may not under any circumstances be relied upon when making a decision to invest in any fund managed by a16z. (An offering to invest in an a16z fund will be made only by the private placement memorandum, subscription agreement, and other relevant documentation of any such fund and should be read in their entirety.) Any investments or portfolio companies mentioned, referred to, or described are not representative of all investments in vehicles managed by a16z, and there can be no assurance that the investments will be profitable or that other investments made in the future will have similar characteristics or results. A list of investments made by funds managed by Andreessen Horowitz (excluding investments for which the issuer has not provided permission for a16z to disclose publicly as well as unannounced investments in publicly traded digital assets) is available at https://a16z.com/investments/.

Charts and graphs provided within are for informational purposes solely and should not be relied upon when making any investment decision. Past performance is not indicative of future results. The content speaks only as of the date indicated. Any projections, estimates, forecasts, targets, prospects, and/or opinions expressed in these materials are subject to change without notice and may differ or be contrary to opinions expressed by others. Please see https://a16z.com/disclosures for additional important information.