“There is a saying that fire and water are good servants but bad masters. To a much milder degree, it may be said that speculation is a good servant but a bad master. It is potent for evil, or it is beneficent, depending on how it is used. It cannot be eliminated. It can be checked. To a certain extent it can be directed into useful channels.” — Speculation and The Chicago Board of Trade (1921)

Regardless of the technology or the era, one aspect of markets is constant: human nature. Consider this quote on the psychology and behavior of speculators:

“I wish to describe the nervous condition of the speculators and the restlessness of their behavior at their business. … The speculator fights his own good sense, struggles against his own will, counteracts his own hope, acts against his own comfort, and is at odds with his own decisions. …There are many occasions in which every speculator seems to have two bodies so that astonished observers see a human being fighting himself …” — Joseph de la Vega, Confusion de Confusiones

The most remarkable part of this description is its publication date: 1688. While the stock exchange in 17th-century Amsterdam is vastly different from the current-day NASDAQ and NYSE, investors’ behavior is all too similar. Yet despite the mountainous historical evidence to the contrary, investors are eternally optimistic that the latest innovation or technology will cure our behavioral shortcomings.

Following 19th-century innovations in communication, for example, one author confidently forecasted in 1874 that the transatlantic cable would “diminish the effects of what we understand by commercial crises.” Just 11 days before the 1929 crash, economist Irving Fisher famously declared that “stock prices have reached what looks like a permanently high plateau.” In interwar Britain, the average investor had an unprecedented level of information and investment choices at their disposal because “the telegraph and telephone meant that it became possible to conduct far more trade remotely from outside London.”

Yet this abundance of information and choice did not lead to a better-informed investing public. Instead, there were more instances of fraud as investors felt paralyzed by choice and entrusted their savings with outside “experts.” There are countless more examples of investors succumbing to the boom-and-bust cycle of speculation.

In modern parlance, this is a feature of markets, not a bug. While there will always be personal losses and hardship for individual investors that get caught out in a mania, the act of speculation is key for driving economic growth and prosperity at the national level. This is summarized well by a quote from The New York Herald in 1854:

“Although much embarrassment has and will continue to result as a necessary consequence to the extravagant speculative mania which has run over the land from one section to another, still we have to record the gratifying fact that, notwithstanding there must be enormous personal sacrifices, the country will, as a whole, derive much benefit from the immense internal improvements which have been undertaken …”

So, what? Instead of wasting resources on initiatives aiming to eradicate speculative manias, we should determine how investors’ innate affinity for speculation can be channeled into productive ventures that benefit society.

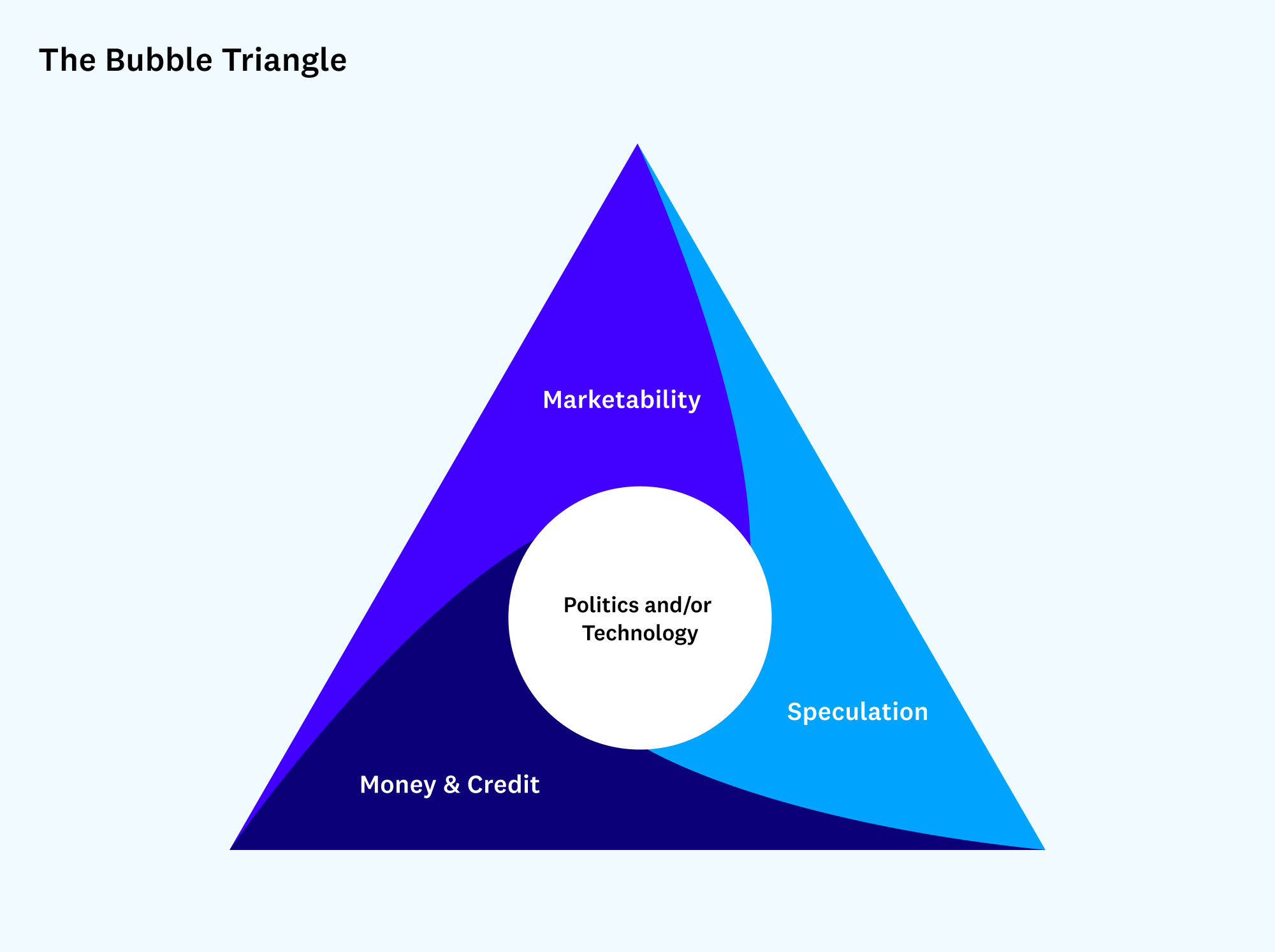

The ‘Bubble Triangle’ and democratizing speculation

In their excellent book Boom and Bust: A Global History of Financial Bubbles, authors John Turner and William Quinn offer a framework for how and why bubbles form. This framework leverages the “Fire Triangle,” made up of oxygen, fuel, and heat: “Given sufficient levels of these three components, a fire can be started by a simple spark. Once the fire has begun, it can then be extinguished by the removal of any one of the components.”

Turner and Quinn’s Bubble Triangle replaces oxygen, fuel, and heat with marketability, money & credit, and, notably, speculation.

- Marketability (the oxygen): “The ease of which an asset can be freely bought and sold. … Another factor is divisibility: if it is possible to buy only a small portion of the asset, that makes it more marketable.”

- Money & credit (the fuel): “Low interest rates and loose credit conditions stimulate the growth of bubbles … bubble assets themselves may be purchased with borrowed money, driving up their prices … low interest rates on traditionally safe assets [i.e., government debt] … push investors to ‘reach for yield’ by investing in risky assets instead … funds flow into riskier assets, where a bubble is much more likely to occur.”

- Speculation (the heat): “The purchase of an asset with a view to selling the asset at a later date with the sole motivation of generating a capital gain … during bubbles, large numbers of novices become speculators … as a fire produces its own heat once it starts, speculative investment is self-perpetuating: early speculators make large profits, attracting more speculative money, which in turn results in further price increases …”

As with the Fire Triangle, removing any one component will extinguish a bubble. Of course, the first — and most necessary — element for the creation of fire is a spark. For the initial “spark” setting Bubble Triangles alight, Turner and Quinn provide two culprits: technological innovation and government policy.

Technological innovation can provide a spark by generating significant profits at firms utilizing new technology, producing large capital gains. These gains attract speculative momentum traders who buy shares because of the soaring stock price. New companies form to capitalize on the excitement, optimism builds, and a “new era” narrative is formed.

Government policy can provide a spark when policy changes raise asset prices in pursuit of a particular goal. (For example, policies to increase home ownership contributed to the housing bubble.) Governments can influence different sides of the Bubble Triangle through policy levers like lowering interest rates, increasing money supply, or deregulation.

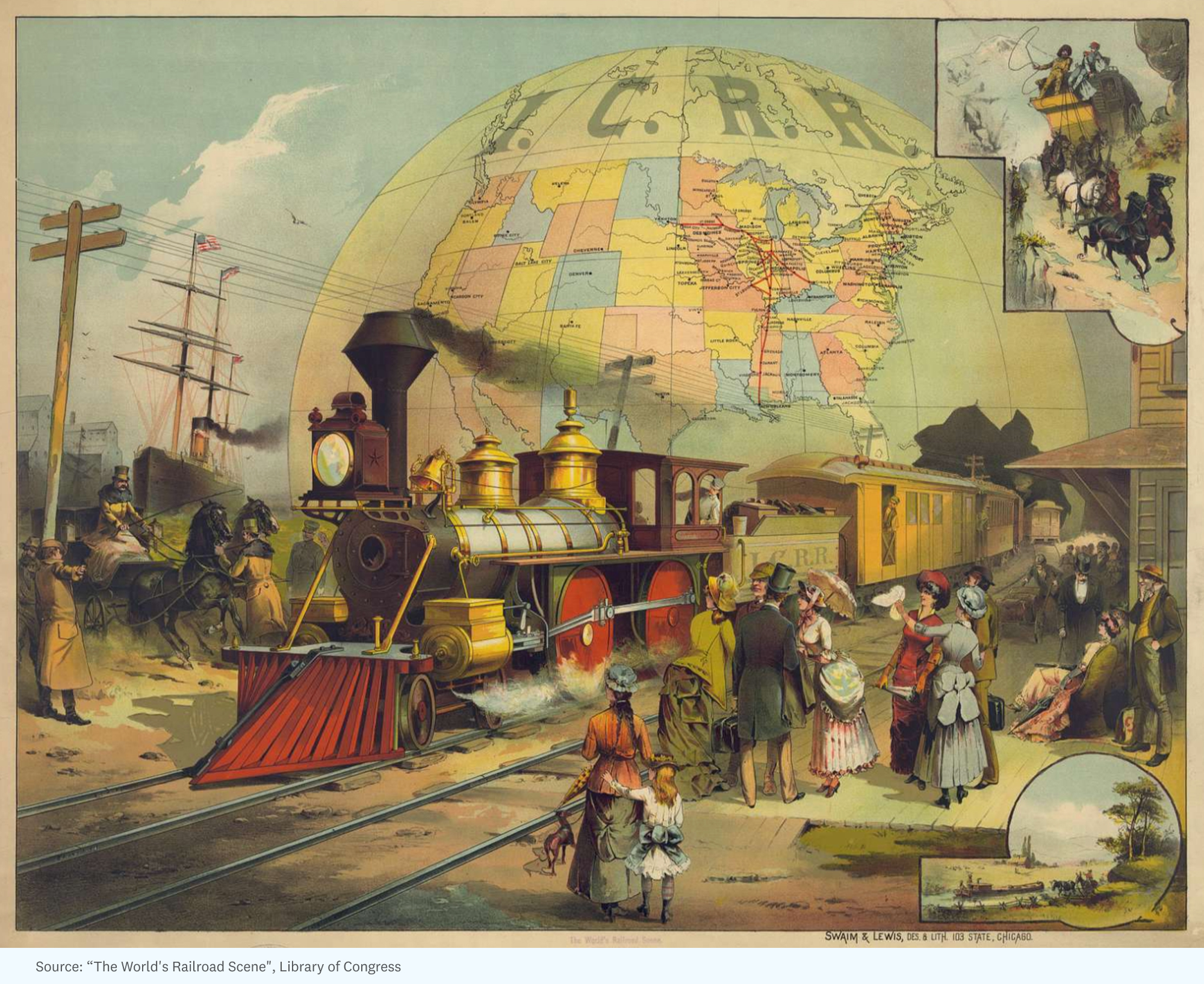

We can study this phenomenon through the creation of America’s railroad system in the 19th century to see what sparked it, and how the interplay of marketability, money & credit, and speculation produced a massive national project that drove America forward.

The Bubble Triangle: Railway mania and channeling speculation

“The history of the ‘Pacific’ railroads of America is almost a romance. In the first instance, their construction was a political necessity … resources of the central portion of the States would be opened up, and a new route would be formed for commerce from Europe to Asia.” (The Elder Pacific Railroads of America, The Economist, May 17, 1884)

Charleston-Hamburg Railroad, the first American line providing regular service, opened its doors on Christmas Day in 1830. That winter morning, 140 lucky passengers experienced a new form of transportation that forever altered America’s economic trajectory. They may not have understood to what magnitude, but contemporaries recognized the societal returns railroads could offer in addition to financial returns.

After completing the 136-mile line in 1833, Charleston-Hamburg’s directors stated:

“Our citizens wisely determined that railroads would be eminently beneficial to the State; that they would revive the diminished commerce of our city and tend to bring back the depreciated value of property … Real estate in and near Charleston had sunk to half its former value … industry and talent had lost encouragement and not met their merited awards…

Stockholders of the ‘South Carolina Canal and Railroad Company,’ especially those who engaged early in the enterprise, must feel that delight in a very eminent degree, when they reflect on the public good they have rendered to this State, and to a large portion of their country, by constructing a railroad from the vicinity of Charleston to Hamburg.”

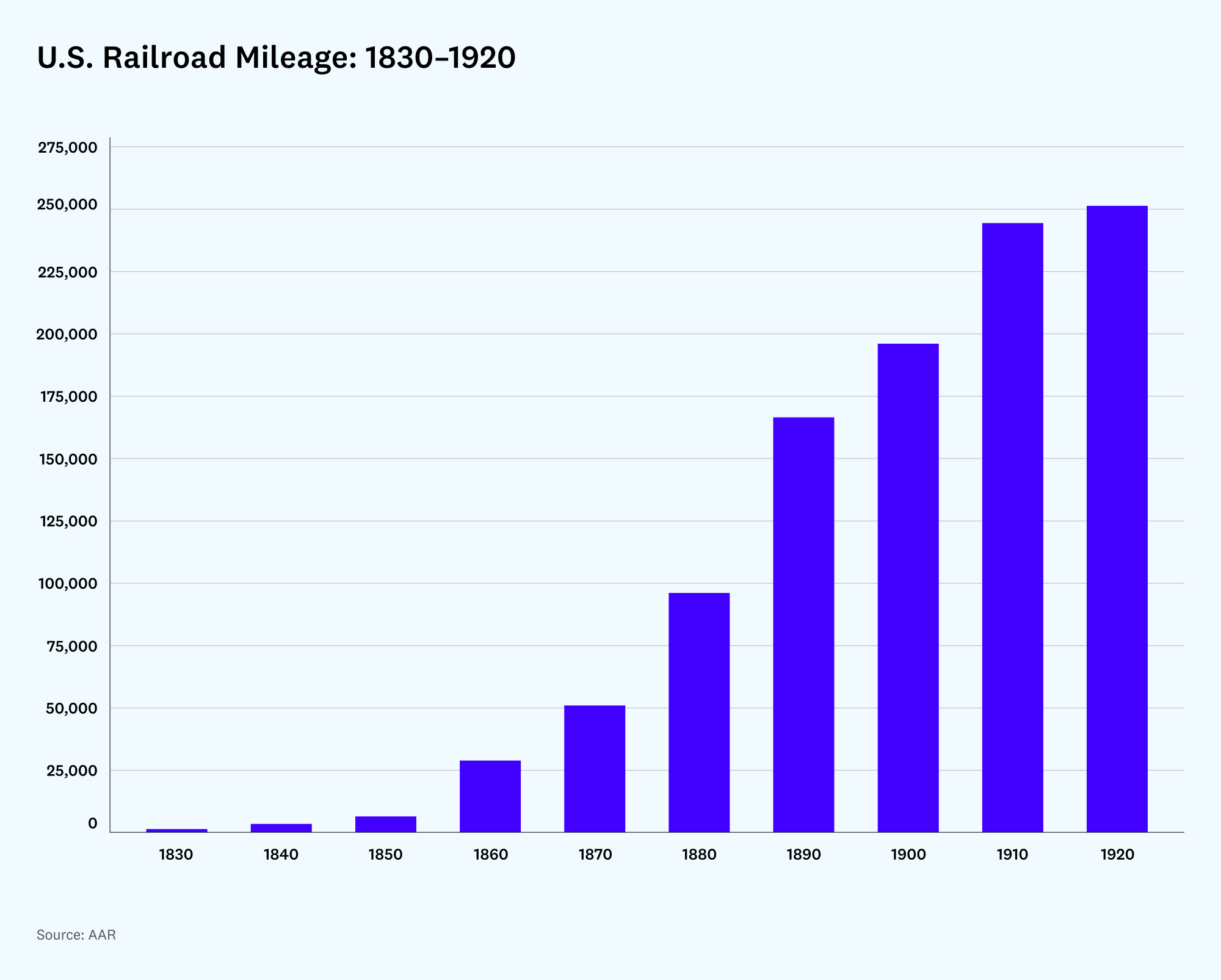

The message was clear: railroads were a public good and an attractive investment. This sentiment reverberated across the country, and by 1840 America had more miles of track than Europe.

Two pivotal moments, in 1849 and 1851, then truly sparked America’s railway boom.

The ‘sparks’: Westward expansion and federal land grants

As with any innovative technology, the “hockey stick” growth in railroads did not go unnoticed by investors. Up to 1850, there had been $372 million ($50 billion) invested in American railroads. From 1850 to 1857, however, an additional $600 million ($80 billion) was invested into this burgeoning new industry.

This explosive growth was fueled by a national obsession with westward expansion after a historic discovery at Sutter’s Mill triggered the California Gold Rush in 1849. California’s population grew from 93,000 to 380,000 over the next decade as Americans and foreigners came searching for gold. When California received statehood through the Compromise of 1850, it became clear that America needed a railway linking its coasts.

The approach to constructing this transcontinental railroad was heavily influenced by the other pivotal moment in America’s railway boom: federal land grants. In 1851, an ambitious young attorney from Springfield helped Illinois Central Railroad obtain a grant of 2.6 million acres, which marked the first federal land grant ever given directly to a corporation.

These may seem like trivial details of government bureaucracy, but this 1851 land deal demonstrated the government’s willingness to induce private investment in railway construction through federal subsidies.

Clearly influenced by the 1851 deal he helped broker, that same Springfield attorney granted 5.5 million acres of federal land directly to railroads 11 years later in the Pacific Railroad Act. That young attorney had become the 16th president of the United States, Abraham Lincoln.

Money & credit (fuel)

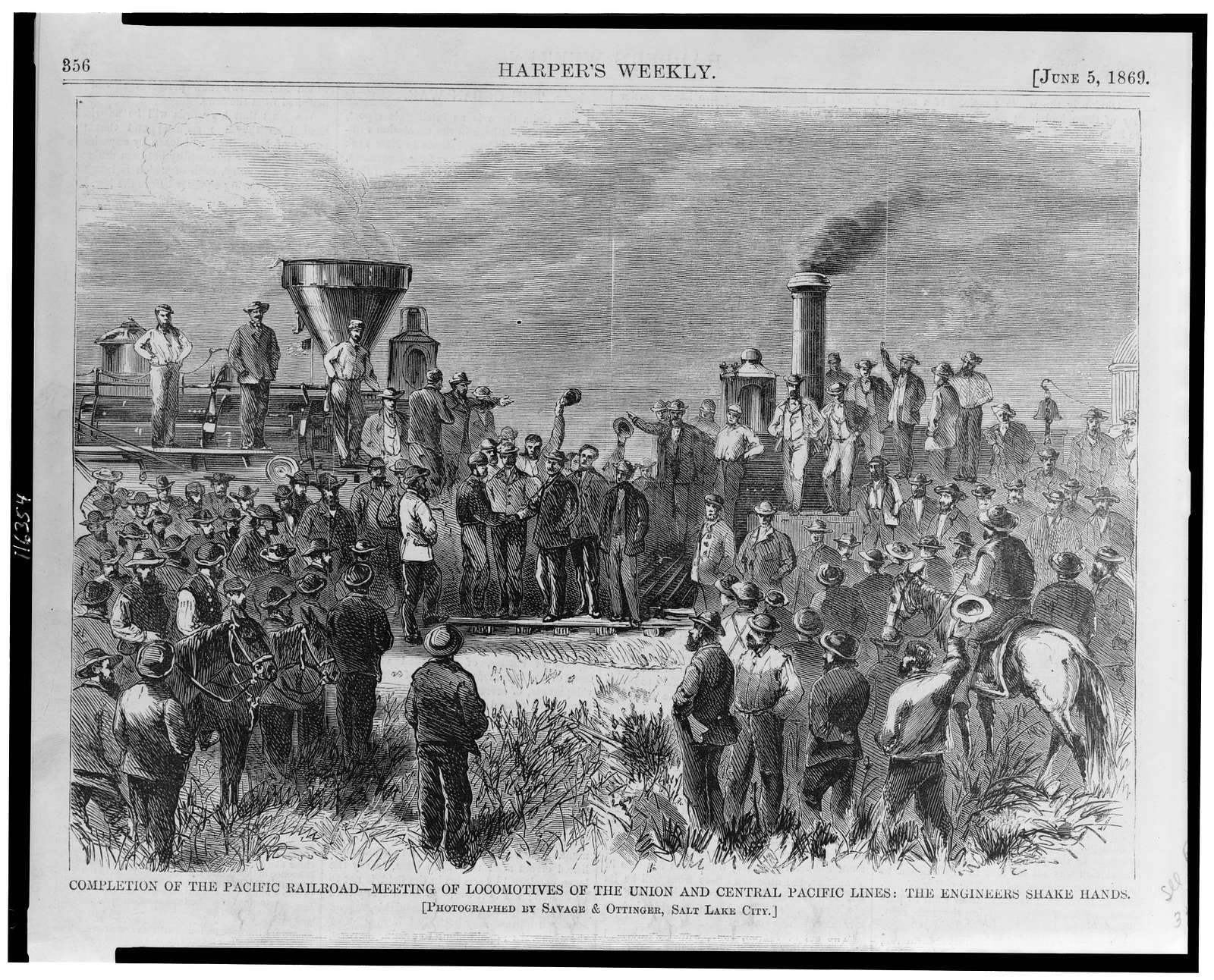

The primary objective of Lincoln’s Pacific Railroad Act was the construction of a transcontinental railroad linking America’s coasts.

“To encourage the railroad companies to build the transcontinental railways, the government gave them 6,400 acres of land (10 square miles) and $16,000 in government bonds for each mile of track laid. Part of the companies’ profit came from selling this land. Therefore they launched a massive sales campaign, offering a settlement package, which included:

- a safe, cheap and speedy journey west;

- temporary accommodation in hotels until the families had built their own homes;

- other attractions such as schools, churches, and no taxes for five years.” (Reasons for Westward Expansion, BBC)

The Union Pacific and the Central Pacific railroads were the two companies tasked with building this incredible railway. Union Pacific’s line would start in Nebraska and build west, while the Central Pacific began in California and built east. The two lines met at Promontory Point, Utah, on May 10, 1869.

The 6,400 acres of land and $48,000 for each mile of railroad track built was a key driver of America’s railway boom. The Pacific Railroad Act also broadly enabled the federal government to provide land grants directly to corporations. This helped attract private investment by lowering the funding costs for expansion and providing financial incentives for beginning construction. The scale of this initiative was simply remarkable (Dan Allosso, American Environmental History, November 2015):

“In the eighteen years between the original Illinois Central grant of 1851 and the completion of the transcontinental line in 1869, privately-owned railroads received about 175 million acres of public land at no cost. This amounts to about 7% of the land area of the contiguous 48 states.”

In the 19th-century railway boom, the government provided both the spark and fuel. While the federal land grants and subsidies were not free of problems — most notably the Credit Mobilier scandal — the approach successfully induced enough private investment to make a large-scale project like building a national railway network possible.

Marketability (oxygen)

The endurance of this railway boom stemmed from its marketability for smaller investors. This key component engendered widespread clamor for railway shares as retail investors could participate in the country’s exciting growth prospects in western territories.

Like all great manias, the railway boom was sustained by speculators’ ability to purchase shares through “installment” plans requiring little money up front (sometimes just $1). Not unlike fractional shares today, lower denominations attracted larger crowds. If some investors could afford a $50 railway share up front, then many investors could buy shares requiring just $1 up front.

As the excitement for railroads and western expansion intensified, newspapers became riddled with investment offerings for new railway lines. One such offering in an 1861 edition of The Lancaster Ledger (“The Central Railroad Must Be Built!!!,” April 3, 1861) in South Carolina demonstrates how railroads emphasized the small up-front cost for buying shares:

Although shares were issued at $50, “no money (except one dollar per share) is needed now and will not be perhaps in a year or two.” Cheap!

Technological advances in communication (i.e., the telegraph) also meant that investors were increasingly aware of the money being made in railway stocks elsewhere, which further encouraged herding behavior. Every day newspapers reported new railway lines and speculators’ profits, as news from across the country arrived by telegraph.

Today, social media similarly helps foster excitement and rallies in popular stocks.

Speculation (heat)

Of course, the last key component of the railway boom and the Bubble Triangle is speculation.

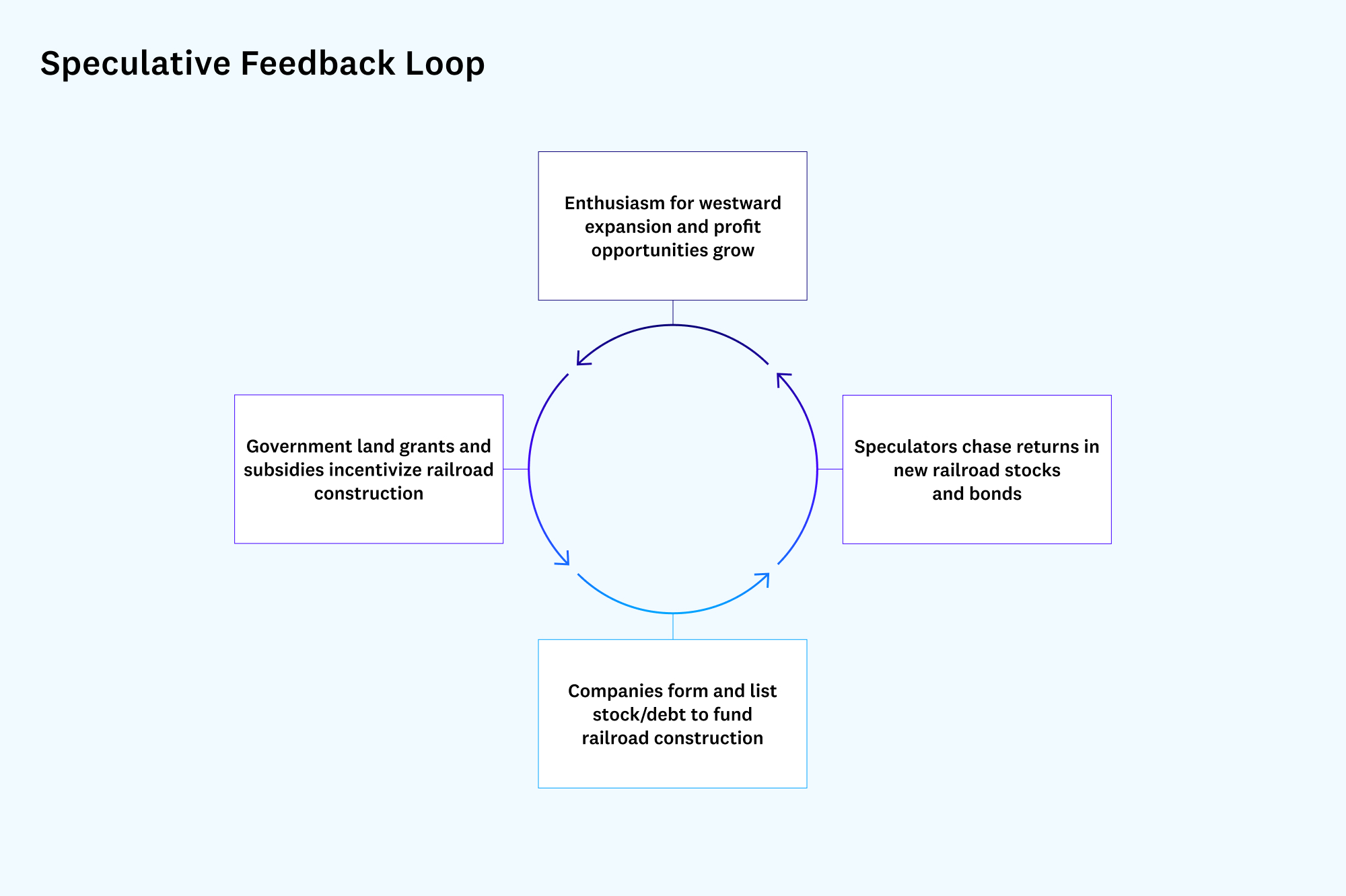

The government incentivized entrepreneurial activity and formation of railroads with specified rewards for miles of track built. In turn, this attracted the speculating public that was enamored by westward expansion and belief in America’s “manifest destiny.” Seeing the returns made in early railroad stocks drew herds of speculators into the stocks and bonds of railroads formed in response to the government incentives.

The amount of speculative activity in railroads is highlighted by the fact that railways lay at the heart of financial panics in 1857, 1873, 1893, and 1901. An excerpt from an 1869 newspaper sums up the period well (“The Dangers of Railway Speculation,” The New York Herald, April 14, 1869):

“The history of our Western railways is a continuous repetition of the old story of imposition upon public confidence. A half dozen stock gamblers form a company, issue their prospectus, induce the public to invest in their bonds or stock, and with the money thus raised build a hundred miles or so of the great line which is to form a connecting link between the important cities …”

Another article from the 1850s highlights how the government itself stimulated speculation (“Highly Curious Financial Views,” The New York Herald, December 3, 1857):

“Under the excitement of its presumed progress, its credit abroad, and its inflated value at home, the West really believed in its own prosperity …

They invited capital to carry out plans for railways over the uninhabited prairie and between unbuilt cities. The market was flooded with railroad schemes; stock was issued, money raised, and the West was tapped at every point, for it was rich enough to pour forth in terminable streams of wealth at every pore …

Congress made extravagant grants of their only tangible resources, real estate, to excite speculation, and thus the railway mania reached its climax …”

The government helped foster speculation in railway shares by playing to the innate behavior of investors. Rather than standing in the way of speculation or trying to curb it, the government took full advantage of it by offering land grants to encourage more railroad companies to form. Investor’s speculative tendencies took care of the rest. Soon, a feedback loop for speculation had formed:

The Bubble Triangle today

How can this example be replicated in markets today, and how have recent initiatives fared? The last 12 months offer examples of “mini-bubbles” in electric vehicle companies, SPACs, cryptocurrencies, NFTs, “meme stocks,” and more. While no single spark ignited all this, emerging trading platforms and the pandemic played large roles.

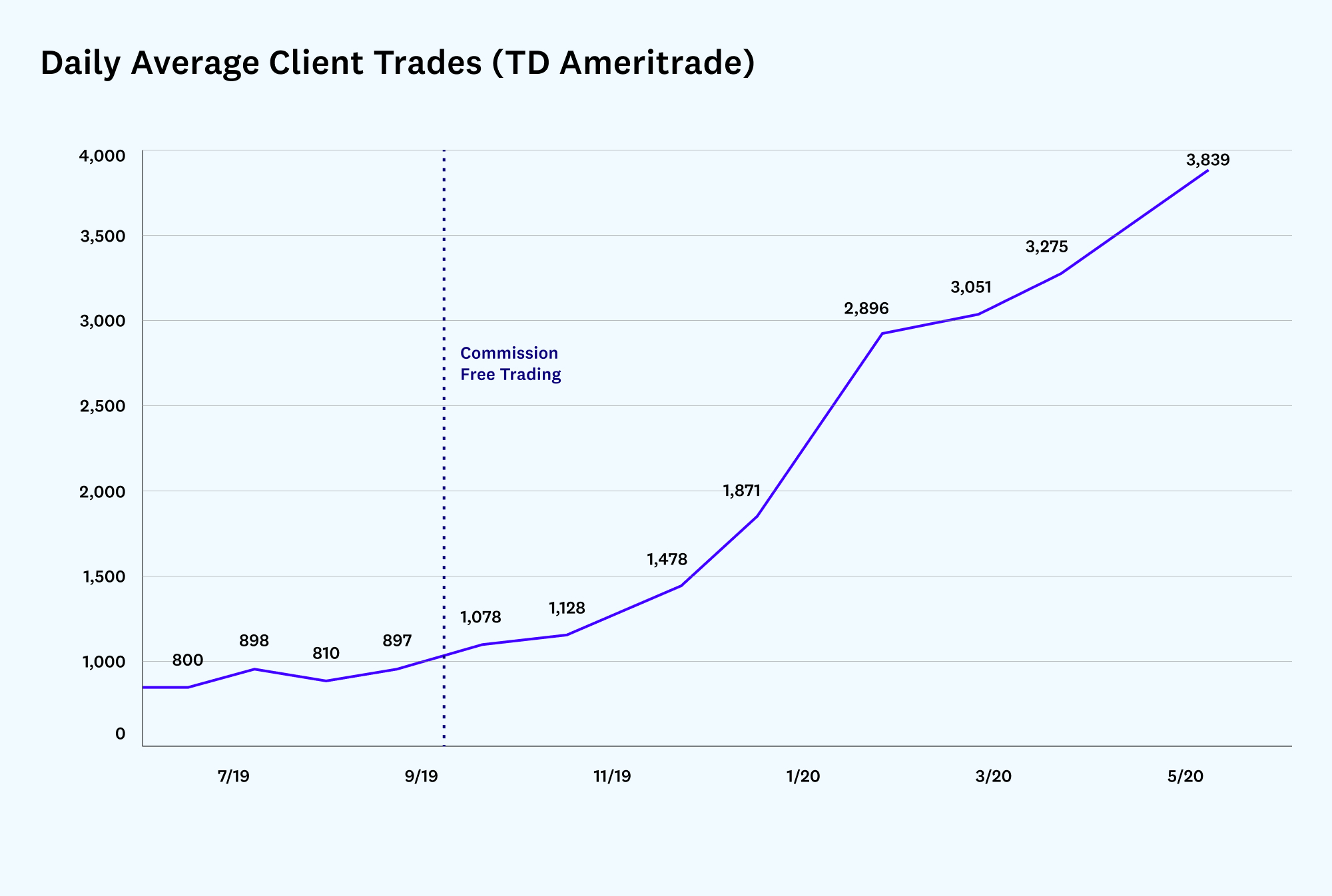

When the barriers to speculating are reduced or removed by technology, speculation abounds. The ability to trade on our smartphones with just a few clicks is the perfect example. Yet, until recently, there was a financial cost to these trades via brokers’ trading commissions. That changed in late 2019 as online-brokerage firms announced commission-free trading. The impact on levels of speculation was practically immediate:

This uptick in speculative behavior exploded during COVID-19 lockdowns as people were stuck at home with nothing to do. Under this paradigm, many turned to speculating on stocks, particularly technology stocks with exciting brands.

Money & credit (fuel)

The fuel for these mini-bubbles was a combination of low interest rates and stimulus checks. Low interest rates have pushed investors into riskier assets — like equities — as bond yields are too low. This dilemma for investors is referred to by a new acronym, TINA: There Is No Alternative [to owning equities].

Government stimulus checks acted as additional fuel, providing millions of Americans with extra cash to spend. CNBC reported that half of 25- to 34-year olds “plan to spend 50% of their stimulus payments on stocks.” With monetary policy encouraging investors to buy riskier assets, and stimulus checks providing capital for investors to deploy, this speculative boom has no shortage of fuel.

Speculation (heat)

Investors have always chased returns after seeing the gains achieved by others, and social media has only exacerbated this behavior. One of the first stocks to capture speculators’ attention in 2020 was Tesla. From the stock’s March 18 low, shares skyrocketed a staggering 590% through August 31 as retail investors herded in. The parabolic returns in a household name like Tesla caused speculators that missed out to search for “the next Tesla.” Social media was awash with posts of new day traders flaunting gains made on Tesla, and others wanted in.

Similar to the railroad companies forming to capitalize on the excitement for railways and western expansion, a wave of SPAC deals involving electric vehicle (EV) companies were announced to seize the moment. One such EV deal involved Nikola Motors, which was briefly crowned as the next Tesla. Despite having no sales or product on the market, shares soared 100% in the company’s first month of trading. It quickly became apparent, however, that any similarities ended with their shared homage to inventor Nikola Tesla, as Nikola’s CEO later stepped down amid allegations of fraud.

Although it’s unlikely that most speculators bought EV stocks for purely environmentally driven reasons, the episode demonstrated that speculative herds could be interested in industries that positively impact society — in this case electric vehicles and reducing fuel emissions. Harnessing speculation might work just as well for all kinds of innovation, and social causes as well.

Marketability (oxygen)

As mentioned, commission-free trading is a key driver of this speculative boom. Removing the financial burden previously associated with overtrading (that is, high commissions) encouraged speculators to continue betting on the short-term direction of stocks and herd into popular trades.

An equally important development was the introduction of fractional shares, which allow smaller investors to buy stocks in fractional amounts. For small investors interested in buying more expensive stocks like Amazon, which can trade at more than $3,000 a share, fractionalization was revolutionary. The ability to buy and sell shares (fractional or whole), commission-free, from one’s smartphone makes this the easiest period in history to speculate.

Channeling modern speculation

If we know how bubbles form using the Bubble Triangle framework, and see evidence that levels of speculation are currently high, how can this speculative fervor be channeled into ventures that benefit society more broadly?

It is helpful to study the success of a recent initiative launched to stimulate investment in underserved communities: opportunity zones. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 created Opportunity Zones to “spur economic development and job creation in distressed communities.” The initiative aimed to stimulate private investment by offering attractive tax incentives for investing in such zones.

However, a key issue with this plan and others like it is that they are difficult (or impossible) for smaller investors to access. Most opportunity zone funds require accredited investor status and have six-figure investment minimums. Like other private “impact fund” investment vehicles, this accredited investor status makes it difficult for a movement to capture the zeitgeist of a speculating public. In the Bubble Triangle, the marketability of an asset (ability to easily buy and sell) is the oxygen that sustains a bubble. Without this oxygen, there is no speculation.

Looking at the booming popularity of environmental-social-governance (ESG) investing in public markets, there is clear demand for investments that offer an element of positive societal impact (or more stakeholder vs. just stockholder involvement). Despite SEC amendments to modernize requirements for accredited investor status in 2020, more extensive changes may be needed to unlock this pent-up demand from non-accredited investors for more access to private markets.

A logical first step for attracting greater levels of private investment for these endeavors is allowing a larger number of people to invest. That said, the net worth requirement for accredited investor status should be reviewed in relation to the level of investor disclosures required for private offerings. Andrew Vollmer, a scholar at George Mason University, argued in a recent paper (Securities Regulation Law journal, October 2020):

“Net worth or income does not provide a rational connection to an investor’s ability to fend for him- or herself by having knowledge of information in a registration statement or having an ability to ask for and obtain the information felt necessary to making an informed investment decision. Income and wealth are not effective ways of identifying the persons who understand the risks of buying securities. An individual may acquire high compensation or wealth in many ways other than actions that provide a basis for evaluating an investment opportunity.” [emphasis added]

Outside of regulatory changes, innovations in technology, finance, and the intersection of both fields present exciting new opportunities for channeling speculation. One initiative from Berkeley, California, offers an interesting example of how to stimulate private and public investment by offering municipal “microbonds” using blockchain technology with investments as low as $25. While only time will tell if this idea catches on, it is encouraging to see innovative approaches to marrying public and private investment in ways that broaden access (marketability) to smaller investors.

***

The 19th-century railway boom marked a successful, if at times flawed, combination of private and public investment in a venture that revolutionized America’s society and the American economy. The transcontinental railway was the largest publicly funded work of the 19th century. With the federal government’s subsidies and land grants helping induce private investment, public enthusiasm for railroads — transcontinental or otherwise — manifested itself in rampant speculation in railway stocks throughout the 19th century.

Economist Jack Kenneth Galbraith stated that “Nothing in the 19th century is more remarkable than the way men forgot the last railroad debacle and proceeded to lose money in the next.” By not erecting barriers between investors’ enthusiasm and their ability to speculate in this national endeavor, the government indirectly helped finance the growth of America’s railways further. While there were many instances of railway fraud and companies going bankrupt as well, the railway system that was built across this nation was a feat that we still look back on for inspiration.

Across centuries, investors’ behavior and predilection for speculation has not wavered. As a society we must decide upon the grand projects we wish to accomplish, and then ensure that the public’s speculative enthusiasm can be effectively channeled into related ventures while trying to limit fraud and chicanery where possible.

I leave the reader with this description of American prosperity and the necessity of speculation (“The Schuyler Frauds,” The New York Herald, August 4, 1854):

“The real capital of the country is in the energy and the enterprise of its people; and with these elements of success everywhere and always active, difficulties are only the stimulus of endeavor.

The Americans have been overtrading and overspeculating ever since they were a nation; their liabilities have always been, more or less, a mortgage on futurity; but they have never yet failed to find a way, wherever they had a will to force them forward in search of it …

They have heavier engagements on their hands at the present time than they can cover without a little embarrassment, but their present embarrassment arises from the investment of capital in enterprises [railroads] that, speculative as many of them may have been, will vastly enhance the available resources and accelerate the future progress and prosperity of the republic.”

Views expressed in “posts” (including articles, podcasts, videos, and social media) are those of the individuals quoted therein and are not necessarily the views of AH Capital Management, L.L.C. (“a16z”) or its respective affiliates. Certain information contained in here has been obtained from third-party sources, including from portfolio companies of funds managed by a16z. While taken from sources believed to be reliable, a16z has not independently verified such information and makes no representations about the enduring accuracy of the information or its appropriateness for a given situation.

This content is provided for informational purposes only, and should not be relied upon as legal, business, investment, or tax advice. You should consult your own advisers as to those matters. References to any securities or digital assets are for illustrative purposes only, and do not constitute an investment recommendation or offer to provide investment advisory services. Furthermore, this content is not directed at nor intended for use by any investors or prospective investors, and may not under any circumstances be relied upon when making a decision to invest in any fund managed by a16z. (An offering to invest in an a16z fund will be made only by the private placement memorandum, subscription agreement, and other relevant documentation of any such fund and should be read in their entirety.) Any investments or portfolio companies mentioned, referred to, or described are not representative of all investments in vehicles managed by a16z, and there can be no assurance that the investments will be profitable or that other investments made in the future will have similar characteristics or results. A list of investments made by funds managed by Andreessen Horowitz (excluding investments for which the issuer has not provided permission for a16z to disclose publicly as well as unannounced investments in publicly traded digital assets) is available at https://a16z.com/investments/.

Charts and graphs provided within are for informational purposes solely and should not be relied upon when making any investment decision. Past performance is not indicative of future results. The content speaks only as of the date indicated. Any projections, estimates, forecasts, targets, prospects, and/or opinions expressed in these materials are subject to change without notice and may differ or be contrary to opinions expressed by others. Please see https://a16z.com/disclosures for additional important information.