Momentum, from an investment perspective, is not a new phenomenon. Since the earliest days of markets, investors have sought to jump on price trends, with the routine drudgery of analyzing fundamentals often taking a back seat.

What has changed is the sheer velocity of momentum, and the dizzying pace that accompanies perceptions of “hot” or “cold” in the marketplace. Trends that used to take years to develop now seem to take months; what used to take days now may take hours, or even seconds.

Given the emergence of new forms of unpredictability, how can we tell whether a downturn is just a normal part of a solid bull market, or the beginning of a major downdraft? Most of us have watched stocks trade lower unrelated to the goings-ons at the company, often because the broader market is under pressure for some reason. Maybe market participants were worried about the next move by the Fed, or maybe they had simply gotten too greedy, driving up stocks to unreasonable valuations.

If the goal is to make sense of, or act on, bull markets and bear markets, we need to have a way to identify when long-term trends are changing.

One way to guard against being caught on the opposite side of a trend in a quickly changing environment is to apply mathematical indicators that can isolate breakouts and trend shifts, while reducing biases that are inherent to investor psychology. In this type of analysis, based on moving price averages, the focus is less on why the market should move up or down, and more on what the current market dynamics are, from a supply-and-demand perspective. In other words, not what the market should be doing, but what it’s actually doing, as a guide to how it might behave in the future.

Reducing the noise with technical analysis

Today there are more opportunities than ever for a decoupling of price from fundamentals. This is fueled in part by a combination of technologically enabled factors, including: 1) the revolution of social media, in which market players can talk up stocks, contributing to upside momentum behind some stocks that perhaps are not deserving from a fundamental perspective, and 2) the incoming generation of retail investors who have access to information and tools that previously were available only to institutional investors.

Technical indicators — based on moving averages of price — smooth out volatility and reduce the noise that characterizes the stock market. We can argue about the fundamental valuation of a company, but we cannot argue with whether its stock is above or below its moving averages.

That’s where MACD, or “moving average convergence-divergence” indicator, comes in. It was developed in the 1970s and is widely accepted by technical analysts as one of the best ways to identify prevailing trends. It is available on just about every charting platform, some free and others at a premium, most of which allow for revision of the indicator’s standard parameters.

The calculation of his trend-following tool is simple. The standard MACD consists of a spread between the 12-period and 26-period exponential moving averages of closing prices for the security in question, which is then smoothed by a signal-generating line derived from the 9-period exponential moving average of the spread.

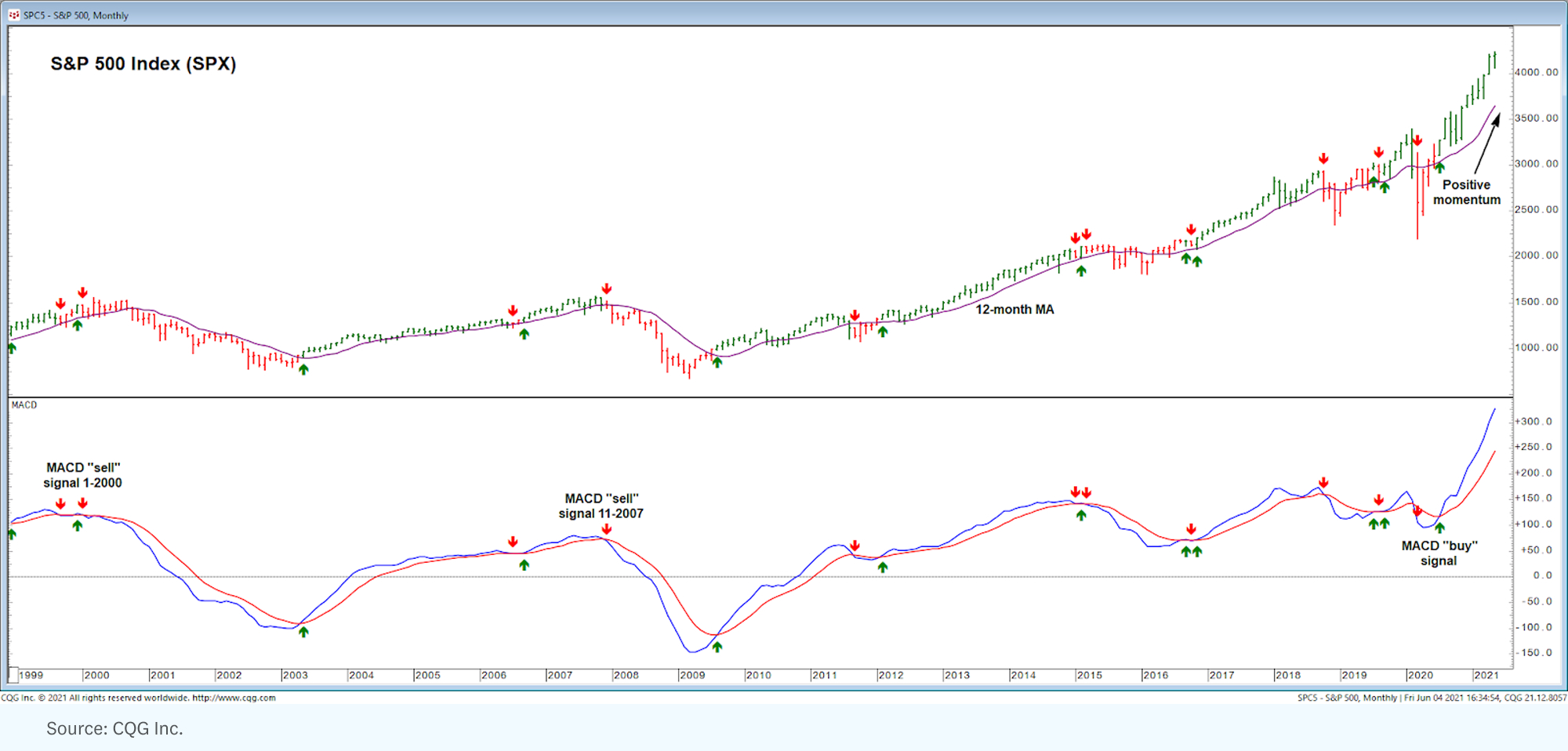

A long-term trend-following overlay is afforded by the MACD applied to the monthly bar chart of the SPX. It provides a visual gauge of the primary trend, rising and falling with it, and it identifies major turning points when the two lines that comprise the MACD cross over. The crossovers provide “buy” signals and “sell” signals that may more clearly indicate when the long-term trend has shifted.

To illustrate this, see the below chart, which dates back to 1999. The price bars are colored green to reflect positive or improving MACD readings, and red to reflect negative or deteriorating MACD readings. Bullish and bearish crossovers, or MACD “buy” and “sell” signals, are denoted by up and down arrows.

Generally speaking, it has been good to be long equities when the bars are colored green, demand is overwhelming supply, and the SPX usually maintains an uptrend. It tends to be a more difficult environment for investors when the bars are colored red, when demand is being met or exceeded by supply, and the SPX usually trends sideways or lower.

Making it easy to avoid bear markets

Technical analysis has been around for more than a century, but it was in 2008 that the discipline seemed to really gain a following on Wall Street. The SPX saw its monthly MACD flash a “sell” signal in November 2007, a month before it broke down, and it did not flash a “buy” signal until a few months after the March 2009 low. The bearish reversal caught many portfolio managers off guard, but those who used trend-following indicators like the MACD were quicker to minimize exposure and saw less damage to their portfolios. This brought attention to the field of technical analysis as a viable discipline for risk management.

MACD “buy” and “sell” signals are often late, occurring after turnarounds because the indicator is derived from moving averages that are lookbacks at price history. However, the signals are not too late to take advantage of long-term turnarounds, and sometimes they even precede bear markets, as in 2000 and 2007. Note that the MACD flashed a “sell” signal in January 2000, before the tech bubble burst, and did not flip to a “buy” signal until May 2003, before a sustained bull market move began. Whipsaws are not uncommon, but they are short-lived, and often associated with shifting trends like in 1999 and 2015, so even false signals can have value. The bulk of uptrends and downtrends were captured by the MACD despite its inherent lag.

Bear markets can unfold abruptly, or after distributive periods that look like trading ranges. Either way, the monthly MACD indicator can identify when the market is likely in the grips of a bear market, or a long-term corrective phase like 2015-2016. It is not a trading system, so a “sell” signal need not be interpreted as a reason to move to 100% cash in a portfolio, but rather an indication of when to position more defensively.

Traders often refine long-term MACDs with shorter-term MACDs, evaluating them alongside other technical indicators that measure momentum and overbought/oversold conditions for a holistic view.

Since technical analysis is based on concrete data, there is broad agreement among analysts on the merits of MACD, although different preferences can be applied in terms of the parameters and time frames that are used.

There are also alternative methods of measuring trends and momentum — for example, simpler moving-averages indicators that do not include a convergence-divergence element, or the Ichimoku system that displays support, resistance, and other trend data. These are often used in conjunction with MACD, for affirmation, and are not viewed as competing systems.

The new generation of investors likely will have increased options to navigate momentum in fast-moving markets. Tools on the horizon will leverage technology to not only access indicators, but to manipulate them and combine them in unique ways to build and test trading systems.

***

So what does MACD tell us about the current environment? As it stands, the SPX is very much in a bull market, according to the monthly MACD. A “buy” signal unfolded in July 2020 after a “V” bottom was established in March 2020 associated with COVID-19. The speed of the recovery rally made the crossover late, but not too late, particularly when enhanced by daily and weekly MACDs. Since the end of July 2020, the SPX has added another 30%, hitting a record high. The MACD continues to support a positive view of long-term momentum, and the two lines that comprise the MACD are still diverging, telling us to keep a bullish bias as we navigate the inevitable short-term swings.

The next “sell” signal from the MACD on the monthly SPX chart will be something to respect based on historical price action. It may not give way to a major bear market, but it would likely be associated with a more challenging trading environment. The top-down risk metric would change our paradigm as it pertains to individual stocks, with breakouts more likely to fail, and breakdowns more likely to see downside follow-through. Overbought readings would instill fear, whereas oversold readings would instill healthy skepticism.

These psychological biases are what makes a market a market — and they can be managed with unbiased input from the MACD. Technological developments will continue to open up markets to new types of investors, but those investors are vulnerable to the same emotional influences that have always driven trends. Fear and greed make a market a market, too. Clear-eyed analysis of the underlying momentum can help us make sense of it all, even at top speed.

Views expressed in “posts” (including articles, podcasts, videos, and social media) are those of the individuals quoted therein and are not necessarily the views of AH Capital Management, L.L.C. (“a16z”) or its respective affiliates. Certain information contained in here has been obtained from third-party sources, including from portfolio companies of funds managed by a16z. While taken from sources believed to be reliable, a16z has not independently verified such information and makes no representations about the enduring accuracy of the information or its appropriateness for a given situation.

This content is provided for informational purposes only, and should not be relied upon as legal, business, investment, or tax advice. You should consult your own advisers as to those matters. References to any securities or digital assets are for illustrative purposes only, and do not constitute an investment recommendation or offer to provide investment advisory services. Furthermore, this content is not directed at nor intended for use by any investors or prospective investors, and may not under any circumstances be relied upon when making a decision to invest in any fund managed by a16z. (An offering to invest in an a16z fund will be made only by the private placement memorandum, subscription agreement, and other relevant documentation of any such fund and should be read in their entirety.) Any investments or portfolio companies mentioned, referred to, or described are not representative of all investments in vehicles managed by a16z, and there can be no assurance that the investments will be profitable or that other investments made in the future will have similar characteristics or results. A list of investments made by funds managed by Andreessen Horowitz (excluding investments for which the issuer has not provided permission for a16z to disclose publicly as well as unannounced investments in publicly traded digital assets) is available at https://a16z.com/investments/.

Charts and graphs provided within are for informational purposes solely and should not be relied upon when making any investment decision. Past performance is not indicative of future results. The content speaks only as of the date indicated. Any projections, estimates, forecasts, targets, prospects, and/or opinions expressed in these materials are subject to change without notice and may differ or be contrary to opinions expressed by others. Please see https://a16z.com/disclosures for additional important information.