Afghanistan. North Korea. Russia. The South China Sea. Open a newspaper these days and you’ll read about the numerous problems facing America’s military. Global threats and a dwindling technological advantage have caused the Pentagon to cozy up to Silicon Valley, a relationship from which Palantir and Anduril are but two successful outcomes. Yet, most dual-use startups building emerging technology still struggle to work with the Defense Department. These companies would do well to spend the summer reading comic books — Iron Man, specifically — and absorbing some of the lessons.

Dual-use startups

Dual-use refers to technologies that have both military and commercial applications.

Made famous by the Iron Man films and comic books, the Marvel superhero Tony Stark, aka Iron Man, is an inventive genius and scion to Stark Industries, who develops and manufactures advanced weapons and defense technologies. The radically innovative products Stark makes, such as the Iron Man suit and advanced aircraft, have been used by the U.S. government in the Marvel Universe to thwart adversaries since 1963. A hallmark of Stark’s innovations is that they are designed to give the Pentagon what it needs, not what it wants.

For a litany of reasons, the U.S. needs Tony Stark innovations more than ever. But in order to create Iron Man-like technology, companies must learn how to optimally engage the Pentagon instead of treating it as just another customer. Using government opportunities can de-risk the challenges technology startups face in both the commercial and defense markets.

The Iron Man model: giving the Pentagon what it needs

The idea of producing defense innovations with minimal Pentagon guidance to meet national security challenges isn’t farfetched. Stark and his company are fictional, but the Iron Man character was inspired by real-life industry titan Howard Hughes, who developed innovations in military aircraft and air-to-air guided missiles, as well as produced the world’s first geosynchronous communications satellites for the U.S. government. It is defense innovations like these, as well as advancements in nuclear research, rocketry, and silicon chips, that fueled the commanding technological lead the Pentagon possessed over competitors from World War II through the early 21st century.

Successful modern defense companies, such as Palantir Technologies and Anduril Industries, were also launched using something like the Iron Man model. Peter Thiel, the co-founder of PayPal, co-founded Palantir in 2004 with the idea that an algorithm could be used to hunt terrorists. Palmer Luckey, founder of Facebook-acquired virtual reality company Oculus, co-founded Anduril in 2017. Anduril applies AI, automation, and edge computing to inform and accelerate defense mission decisions.

Both companies provided the government with needed capabilities. Palantir’s platform was not what the Pentagon wanted to build, but it outperformed the government-driven contender while saving it a fortune. Anduril’s counter-drone technology, also developed on the company’s dime (not the government’s), recently won a $1 billion contract from Special Operations Command (SOCOM) to revolutionize how the command conducts operations.

However, while the ingredients to the Iron Man recipe are straight-forward — (1) civilian entrepreneurs (2) using their own money to develop high-risk capabilities in unproven technology sectors (3) outside of government organizations and requirements (4) to fill a government use-case — the model is neither scalable nor repeatable for one simple reason: very few companies have billionaire founders.

Nevertheless, the lessons from these extraordinary successes can be applied to non-billionaire-founded dual-use companies if those companies consider the Defense Department as a means of expanding development runways. Using government dollars to do this means leveraging myriad government opportunities — from R&D to prototype to production contracts — to expand funding and scale. Dual-use companies can do this by following three tried-and-true strategies:

- Securing government funding through various channels, to grow and scale on the defense marketplace

- Selling unmodified commercial products to the defense industry before adapting them for defense requirements

- Fully assessing the market opportunity across a wide-ranging collection of agencies and organizations

Increasing the opportunity to produce novel solutions

Prior to WWII, the Defense Department developed and built all mission-essential materiel in U.S. shipyards and arsenals. It knew exactly what it needed and how to develop it. Prescribing the development pathway was, consequently, necessary to ensure that commercial companies delivered what was needed at a reasonable cost. The process of prescription was how the defense acquisitions system originated. It is also where prime contractors like Boeing and Lockheed Martin, for example, were born.

Today, however, technology is moving fast and the Pentagon is not always on top of recent developments. Sometimes, it can be aware of technologies but unaware of their impact on the battlefield (e.g. terrorist use of commercial off-the-shelf drones). Therefore, prescribing narrow technological specifications for unknown solutions to benefit unknown use-cases is counterproductive. The Defense Department is aware of these limitations and has established a host of organizations, programs, and opportunities to improve how it works with companies. This is good news.

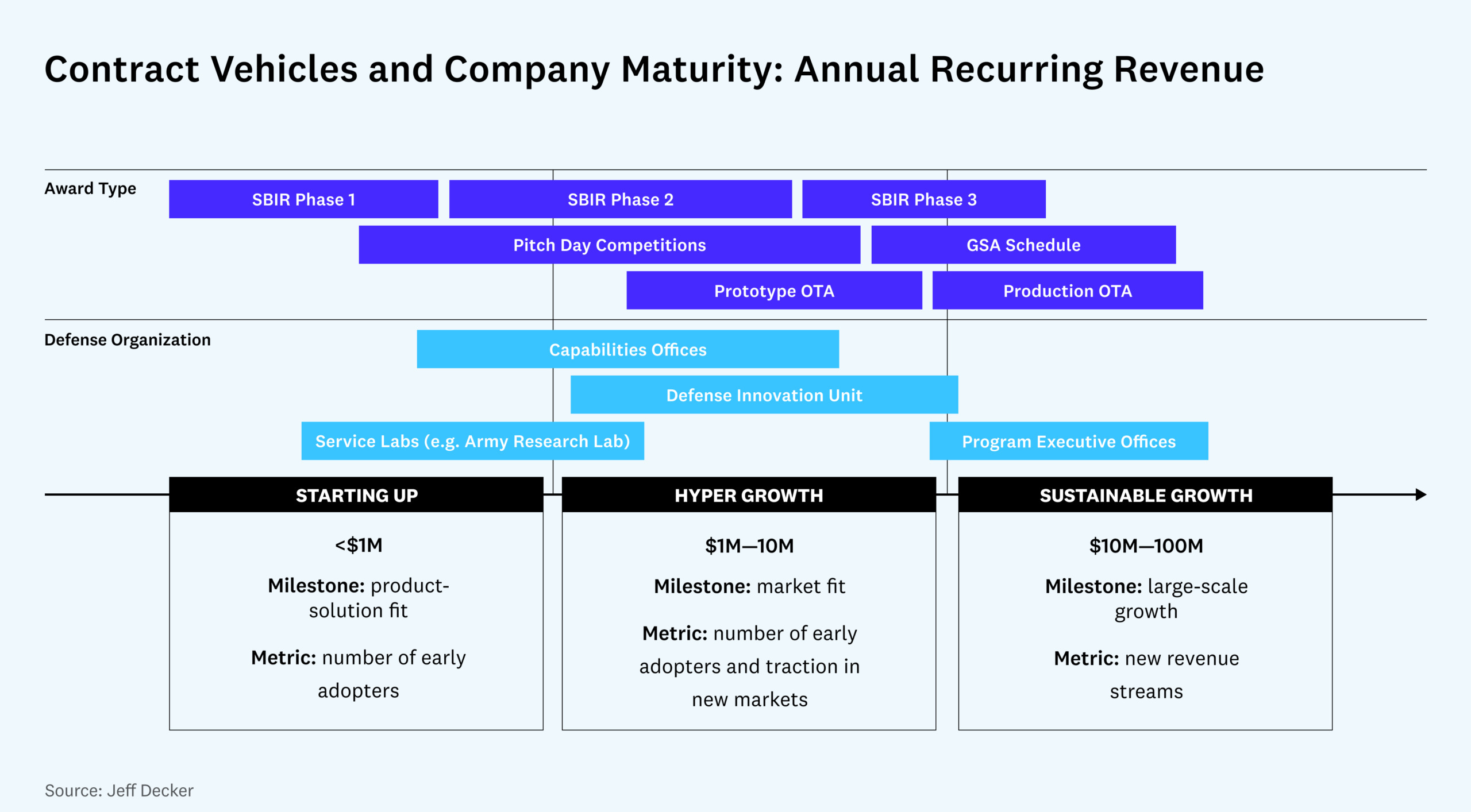

Since 2016, the Pentagon has revitalized the use of older mechanisms such as Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR), Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) awards, and Other Transaction Agreements (OTAs) to procure commercial technologies. In 2021, federal agencies obligated$3.8 billion to nearly 7,000 companies under the SBIR/STTR programs to test whether technologies were feasible in government use-cases. $1.6 billion was awarded through Defense Department SBIR/STTR. SBIR/STTR awards are non-dilutive and range from $50,000 to $1.7 million depending on the phase of the award and the awarding service. Moreover, SBIR/STTR funding gives companies a toehold in the defense marketplace by allowing the government to award them contracts without having to compete in the open market.

The Pentagon has also expanded the use of OTAs, which were first established in the 1950’s under NASA. OTAs serve as the bridge between R&D activities and procurement. They are the contracting backbone for prototyping programs like the Defense Innovation Unit (DIU) and Joint Interagency Field Experimentation Program (JFIX), as well as prize competitions like xTechSearch and TechStars. OTA prototype awards can range from $250,000 to $50 million. These programs help the Defense Department learn about potentially game-changing technologies while providing companies with user feedback useful to inform development in both the commercial and defense markets.

One of the most alluring characteristics about these programs is that the OTA prototype contracting mechanisms behind them are designed to lead into full-scale production contracts worth anywhere between $1 million and $1 billion if the company is capable of proving its value for a defense need. Anduril, for example, was able to turn an OTA prototype valued at $5.1 million through DIU into a OTA production contract with Special Operations Command (SOCOM) worth $99.95 million.

The issue for dual-use companies, though, is that although a menu of defense opportunities exists, very few of those companies are able to navigate them successfully; they lack the manpower and defense sector know-how. But it can be done.

Anthro Energy, a non-billionaire-founded startup in the lithium-ion battery space, is an example of what can go right when defense opportunities are appropriately aligned. Born out of the Hacking for Defense (H4D) course at Stanford University, Anthro Energy found product-defense market fit with its flexible, safe, and high-performance batteries. H4D taught Anthro Energy how to navigate the defense ecosystem and engage with defense customers. Engagement led to developing special operators as their customer, which then informed the development of Anthro Energy’s wearable battery design.

Following the class, the company participated in and was funded through the Army’s xTechSearch competition before being awarded $600,000 from the newly formed National Security Innovation Capital (NSIC). Anthro Energy used NSIC funding to commercialize the technology it designed for SOCOM customers. The company is currently positioning itself to leverage DIU OTAs, and is constantly using Defense Department funding to advance its commercial and federal products.

Classes at universities are just one example. NSIN, for example, is a defense organization offering a range of programs connecting companies with military personnel, as well as with funding to help entrepreneurs build prototypes. Other organizations, like Parallax Research, are funded by the government to help companies tackle the defense marketplace.

Selling commercial products before designing bespoke defense capabilities

There are two principles for deploying solutions in the defense market: (1) Anything less than a 100%-finished solution is unacceptable for non-R&D contracts, and (2) defense-customer acquisition is more time-consuming and resource-intensive than in the commercial market.

Still, some dual-use companies that aren’t interested in cobbling together awards tend to approach the defense marketplace with the same logic they’ve used to generate success in the commercial marketplace, by either shipping an unfinished product and iterating, or by gaining user feedback to design a 100%-finished solution. As stated above, the former is a nonstarter because the Defense Department is risk-averse (and rightfully so).

That being said, developing a 100%-finished solution to the exact specifications of a solicitation, or directly in line with feedback from end-users, and expecting to line up several contracts is also misplaced commercial logic. There are two issues with this logic in the defense sector:

- End-users rarely purchase products. Customer acquisition in defense actually requires sign-off from at least three stakeholders: end-users, buyers, and decision-makers — who are almost always in different geographical locations and typically do not know one another.

- End-users, buyers, and decision-makers tend to view the problem and solution differently. As a result, additional feature requests are piled onto product specifications, thus costing the company additional time and money. This makes engineering a 100%-finished solution and expecting a sale a risky proposition.

The fictional Iron Man model navigates these issues by using billionaire wealth to de-risk technological solutions before the idea is pitched. Dual-use companies without billionaire founders can’t take this risk, but they can replicate the model by selling their commercial product to the Pentagon without making any — or at least any significant — modifications. Commercial sales to the Defense Department generate revenue and let users experience the product before any resources are spent on modifications.

For example, Learn to Win deployed its unmodified professional-sports training platform to Air Force pilots. After having sold the commercial product to the Defense Department, the company began tailoring its platform for specific defense uses such as helping military personnel identify corrosion, track weather, and train pilots. Learn to Win is now being used by 7,000 uniformed personnel.

The path to doing these deals should begin by searching for Commercial Service Offerings (CSOs), which describe defense problems without prescribing exactly what the solution should be. The Defense Innovation Unit (DIU) pioneered and uses CSOs to achieve its mandate of “accelerat[ing] the adoption of leading commercial technology throughout the military and growing the national security innovation base.” DIU director Mike Brown is supportive of the Pentagon purchasing unmodified commercial products because they ensure that the government has the latest technology, while also giving users the opportunity to determine modifications that better suit their needs. Another path to selling commercial products is through prototyping programs that don’t dictate what the solution should be.

Importantly, these types of contracts occur before the government makes a large strategic procurement, and can help prevent government stakeholders from adding on “nice-to-have” features that have historically crippled projects by ballooning budgets and making them technically infeasible (e.g. the F-35 and DCGS-A).

Assessing market opportunity

Some dual-use companies, however, will struggle to enter the defense marketplace with their commercial product. For instance, it may appear that a machine learning algorithm requires minimal modifications and simply needs to be uploaded onto government servers, or that a commercial drone only needs to be painted camouflage. This rarely happens and is more likely to be seen in a comic book.

Billionaire-funded companies succeed because they have the financial heeling to build an innovative defense solution and the manpower to generate a market for the product. Establishing a defense market is also essential to dual-use companies, but they can’t generate a market. Instead, dual-use companies must anticipate success and establish the market by identifying and aggregating customer segments within the Defense Department.

Companies must, therefore, de-risk the defense market by ensuring that the total available market (TAM), serviceable available market (SAM), and serviceable obtainable market (SOM) warrant the price of up-front defense modification and licensing costs. But identifying these data points requires companies to determine if/how their product’s value proposition(s) align with end-user, buyer, and decision-maker needs. Identification is extremely difficult and time consuming because dual-use companies must locate these stakeholders within the 2.2-million-person Defense Department. A central repository of problems, and the people that experience them, does not exist.

What does exist is SAM.gov, which publishes all open government solicitations and is highly inaccurate when it comes to estimating the total potential value of the defense marketplace. Put simply: Solicitations indicate single-organization needs but turn out to be poor indicators because they only reference one government organization in need of the solution, even though the problem might be more systemic. Unfortunately, there are no shortcuts and market reports on the defense marketplace do not exist. It is up to companies to piece together disparate customers to forecast the value of the defense market.

So, dual-use companies that don’t want to apply for awards and can’t make an unmodified commercial sale must do the hard work of talking to potential defense end-users to assess their needs and validate that the company’s solution is capable of meeting those needs. In order to have outsized, Iron-Man-scale impact, these companies will also need to read strategic doctrine (e.g. National Security Strategy (Interim), National Defense Strategy, National Military Strategy, Air Force, Army, Navy, Marine Corps) to determine the metrics of success, and then speak to buyers and decision-makers to ensure that helping end-users accomplish their task (product-task fit) translates into mission achievement (product-market fit).

Before entering the defense marketplace, for example, Snorkel AI believed its machine learning software could save defense and intelligence analysts hundreds of person-months of time for each application. It based this belief on years of research and testing funded by the Defense Department. However, the company also engaged with intelligence analysts and leadership in order to verify that its product would actually fit into analyst workflows and that any time savings were indeed beneficial to the wider organization. This allowed Snorkel AI to assess the defense marketplace TAM by calculating the number of defense and intelligence organizations conducting analyses, and then estimating the budget each of these organizations spent on software for analysts.

These efforts and defense customers helped make Snorkel AI a unicorn. Its federal team is currently scaling the platform across the government and Defense Department.

Scaling defense innovation

The solution to America’s national security woes are tied to unlocking defense capabilities from the commercial market. Lessons from the Iron Man model successfully followed by Palantir and Anduril can apply to dual-use startups. However, the lessons for dual-use companies are predicated on using Defense Department opportunities to maximize efficiency and minimize risk by cultivating the Pentagon as a partner. Assessing the defense market, identifying and developing a defense roadmap of opportunities, and selling unmodified commercial products will lengthen a company’s commercial and defense runway.

Companies wishing to deliver value to the Defense Department and tap its significant budget, would do well to heed Iron Man’s words: “Heroes are made by the paths they choose.” Defense go-to-market strategies are unique to companies and their products. Applying the three Iron Man lessons will inform the defense pathways a company takes, yielding increased revenue and greater defense capabilities and a stronger economy — all of which are necessary to prepare for and react to an ever-changing world and shifting geopolitics.

Views expressed in “posts” (including articles, podcasts, videos, and social media) are those of the individuals quoted therein and are not necessarily the views of AH Capital Management, L.L.C. (“a16z”) or its respective affiliates. Certain information contained in here has been obtained from third-party sources, including from portfolio companies of funds managed by a16z. While taken from sources believed to be reliable, a16z has not independently verified such information and makes no representations about the enduring accuracy of the information or its appropriateness for a given situation.

This content is provided for informational purposes only, and should not be relied upon as legal, business, investment, or tax advice. You should consult your own advisers as to those matters. References to any securities or digital assets are for illustrative purposes only, and do not constitute an investment recommendation or offer to provide investment advisory services. Furthermore, this content is not directed at nor intended for use by any investors or prospective investors, and may not under any circumstances be relied upon when making a decision to invest in any fund managed by a16z. (An offering to invest in an a16z fund will be made only by the private placement memorandum, subscription agreement, and other relevant documentation of any such fund and should be read in their entirety.) Any investments or portfolio companies mentioned, referred to, or described are not representative of all investments in vehicles managed by a16z, and there can be no assurance that the investments will be profitable or that other investments made in the future will have similar characteristics or results. A list of investments made by funds managed by Andreessen Horowitz (excluding investments for which the issuer has not provided permission for a16z to disclose publicly as well as unannounced investments in publicly traded digital assets) is available at https://a16z.com/investments/.

Charts and graphs provided within are for informational purposes solely and should not be relied upon when making any investment decision. Past performance is not indicative of future results. The content speaks only as of the date indicated. Any projections, estimates, forecasts, targets, prospects, and/or opinions expressed in these materials are subject to change without notice and may differ or be contrary to opinions expressed by others. Please see https://a16z.com/disclosures for additional important information.